Happy Monday, all my dear Screamers and Screamettes.

If you're anything like me, you're sitting at some desk, rapidly depleting the admittedly scant reserves of interest-in-work you built up over the weekend, and wondering how anybody ever agreed to this whole "labor" model of existence in the first place.

In the words of my beloved Devo: "Toil is stupid."

So, let's you and me take a short break. Just slide on your headphones, let the work sit for a moment, and enjoy a little rock and or roll from The Hives. You deserve it and, honestly, screw the Man. He can clear out his own damn outbox for once!

Enjoy The Hives' "Abra Cadaver":

Monday, June 30, 2008

Friday, June 27, 2008

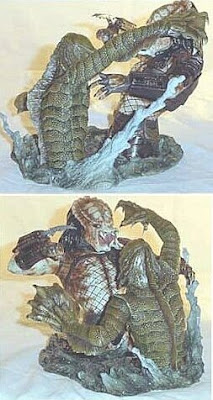

Stuff: Even I, Lucas, have heard the legend of the Fish-Man. And I, Lucas, have a small statue of him fighting the Predator too.

It's been way too long since I've indulged in any Creature from the Black Lagoon goodness, so I give you something to waste those last few moments of the interminable Friday workday afternoon: a link to a nice gallery of Gillman models – from the goofy, such as the Creature's Crate above, to the kind-of-badass, such as the Creature versus Predator statue shown below. Be sure to check out the bizarre female creature models. Though it has always been a fragment of the beast's sad legend that he is, in fact, the last of his kind, model makers can't seem to resist giving the Gillman a she-creature sea creature to hang with. Inexplicably, these she-creatures always seem to have breasts, suggesting that these fish folk nurse like mammals. Too weird to think about. Have fun this weekend, my little Screamers and Screamettes.

It's been way too long since I've indulged in any Creature from the Black Lagoon goodness, so I give you something to waste those last few moments of the interminable Friday workday afternoon: a link to a nice gallery of Gillman models – from the goofy, such as the Creature's Crate above, to the kind-of-badass, such as the Creature versus Predator statue shown below. Be sure to check out the bizarre female creature models. Though it has always been a fragment of the beast's sad legend that he is, in fact, the last of his kind, model makers can't seem to resist giving the Gillman a she-creature sea creature to hang with. Inexplicably, these she-creatures always seem to have breasts, suggesting that these fish folk nurse like mammals. Too weird to think about. Have fun this weekend, my little Screamers and Screamettes.Thursday, June 26, 2008

LoTT-D: Fresh meat.

The League's got two new members. That's right. We're spreading around the League logo like a bad case of athlete's foot in the boy's locker room . . .

The League's got two new members. That's right. We're spreading around the League logo like a bad case of athlete's foot in the boy's locker room . . .And speaking of the boy's locker room: Permit me to introduce Billy Loves Stu: the blog for "homos who love horror and the non-homos who love them." Dude, did you know there was a Leather Pride Flag (pictured above)? If you read B Hearts S, you would. It's actually kinda cutesy for leather types, I think. But my personal feelings about the design of the Leather Pride Flag aside, blog-master Pax Romano is an insightful and clever writer whose posts are well-worth your attention.

The League also welcomes Jeff Allard: the man, the myth, the legend behind Dinner with Max Jenke. Alllard's an experienced horror writer. His work has appeared in newspaper columns, fanzines, online sites, and more. His main love is 80s horror cinema, but his tastes are wide-ranging. When you're tired of the amateur ramblings here, go all-pro with Din-din with Maxie J. You'll want seconds.

Wednesday, June 25, 2008

Stuff: I know all there is to know about The Torture Game.

Actually, I was completely ignorant of the topic until very recently.

Actually, I was completely ignorant of the topic until very recently.Yesterday I received an email from fellow LOTT-D member Absinthe of Gloomy Sunday fame. It contained a link to a thoughtful piece by the whimsically named Winda Benedetti, the "Citizen Gamer" columnist for MSNBC. In the column, Ms. Benedetti takes a look at The Torture Game and its more popular and grisly sequel, The Torture Game 2.

The article links to game, should you wish to try your hand at abusing the nameless victim pictured above. I do believe, though I have not tried it myself, that you can customize the face; this is a boon to those finicky gamers who derive no pleasure from torturing strictly anonymous and generic victims. Ms. Benedetti describes this fairly simple game thusly:

Here, a pale, androgynous human hangs from ropes on the computer screen before you. Among the devices at your disposal — a chainsaw, a razor blade, spikes, a pistol … and a paintbrush (take that!)

There’s little in the way of instructions and no points to be earned. Instead, this dangling ragdoll offers you a canvas to do with what you will — stab him with spikes, flay the skin from his body with a razor, pull his limbs off with your bare hands, paint him every color of the rainbow. No matter what you do to him, he never screams and his expression never changes. He only utters a vague “uuungh” when you’ve inflicted enough damage to kill him.

And that’s pretty much it.

I would only add to this that the victim is not exactly androgynous. He is clearly a he. Even Benedetti uses the masculine pronoun for the victim throughout the article. The awkward use of the term androgynous reflects the fact that, like a Ken doll, he possesses a smooth patch of blank flesh where his sexual organs should be. This underscores an odd detail regarding media torture that I completely overlooked in my series of post on so-called torture porn films: torture porn, in films and games, are remarkably sexless.

Sadly, sexual abuse and rape are a fact of torture. The photos out of Abu Ghraib, themselves a sort of "game" in that they seem to have been staged by the soldiers for the purposes of entertainment and were not a record of standard interrogation procedure, are a brutal reminder of this. Soldiers at the prison made their charges simulate and perform sexual acts on one another. They photographed them in various stages of nudity. In what is perhaps one of the most infamous photographs, PVT Lynndie Rana England, cigarette dangling from her lips, uses both hands to point at the penis of a naked prisoner who is being forced to masturbate for the camera.

By contrast, few examples of torture porn, either in film or in video games, incorporate this. This may sound odd considering Hostel's affection for the nubile flesh of Eastern European co-ed's, but one of the most obvious consequences of the extreme imbalance of power that exists in a torture situation – rape and sexual abuse – rarely figures in. None of the Saw films feature sexual violation or humiliation as a component of Jigsaw's traps. In fact, when sex does appear in the Saw films, Jigsaw's violence is usually presented as a scourge meant to punish the perverse or purify the sexually corrupt (among his victims we find a prostitute, an adulterer, and a producer of violent kiddie porn). In the Hostel franchise, the second film features the threat of a rape that is not, ultimately, carried out and ends in the castration of the would-be rapist, as if he was being punished for taking the act of torture into a still somehow taboo realm of sexual violation. Captivity, perhaps the most nakedly sexualized of the torture porn flicks, is still weirdly virginal. The victims are pretty women, but their trials are strictly non-sexual and, curiously, meant to de-sexualize them: good-looking women get their faces melted off, for example.

Why are our fantasies of torture so sexless? I'm not sure I have a good answer.

The limitations are not technical. Graphic sexuality, though never as popular with gamers as graphic violence, would be nothing new to the world of film or video games. In fact, there's a steady, if mostly non-mainstream, history of sexual violence in video games stretching back to the 2600s bizarre Custer's Revenge - in which you dodged arrows in order to rape a Native American woman (at least, we're told that's what was happening – it was the 2600 and every looked pretty vague) – and running all the way up to the modern GTA franchise – in which players are rewarded for killing prostitutes. If sex organs are missing from The Torture Game 2 it is only because the game's programmer didn't want them to appear.

Perhaps the barrier is strictly social. Sexual violence remains beyond the pale in a way non-sexualized violence does not. As a culture, we have shown a remarkable capacity for rationalizing and defending real and imagined violence: it must exist in the real world for security, as a bulwark to social order, to maintain the law, as reflection of our immutable animal nature; it must exist in the fictional world for catharsis, to reflect the facts of the real world, to give vent to primal urges suppressed for the sake of society. But add a sexual element to that violence and we sense that the field shifts. We're dealing with a different sort of taboo. We either play dumb or reject it. In the former case, we call it camp, stress its unimportance, or otherwise reject the notion that it carries with it the weight of representation. Could anybody enjoy Ilsa: She-Wolf of the SS if they could not dismiss the idea that the film was a sincere and genuine sexualized exploitation of the Holocaust? Has any positive reviewer of that film ever just come out and said, "What really gives Ilsa its kick is that, in the back of the viewers' minds, we cannot dismiss the knowledge that we're desecrating the mass graves of 6 million Jews"? Ironically, our enjoyment of "exploitation" cinema might rest on the mental judo trick that we simply disbelieve that it is really exploitation in any fundamental way. In the latter case, we morally rebel. It is hard to imagine, for example, anybody arguing that, unfortunate as the sexual abuse at Abu Ghraib was, it was essential for national security. (In fact, right-wing defenders of the administration attempted both lines of reasoning: claiming that the abuse was the product of a few morally reprehensible bad apples and dismissing it as part of a meaningless "frat-like prank.") However, that same excuse is regularly offered for all manner of excessive violence – from civilian casualties to support of violence regimes to brutal interrogation techniques – provide it doesn't carry the added taint of sex.

Then again, it may have to do with the real appeal of torture porn being something almost pre-sexual. Benedetti writes:

Unlike most video games that come with a healthy dose of hack-and-slash, “The Torture Game 2” offers no story to give context to your actions. Your victim … he’s simply hanging there, waiting for you. Meanwhile, the game’s ragdoll physics lend a sickeningly hypnotic charm to the whole affair. With every touch of your cruel hand, every cut of the chainsaw, your victim sways, bounces and dances like some fleshy marionette.

This description reminded me of Freud's story of the fort/da game. There's something strangely comforting, regressive, and almost innocent about the fantasy of complete power. The Torture Game 2 speaks to this fantasy by what it leaves out. The victim can't talk. If he could plead and beg, it would be clear that his entire existence isn't simply predicated on your will. The victim is also sexless. This allows players to avoid that most taboo and anxiety-ridden area - an area that brings with it the danger of an implicit recognition of the fundamental and irreducible otherness of people.

These are, of course, just random thoughts. I'd be curious to hear y'all's take on this.

Monday, June 23, 2008

Music: Oh The Horrors, The Horrors . . .

Morning, Screamers and Screamettes, welcome to another work week. To pep you up, I thought mayhaps you'd dig a little goth-infused neo-garage punk from our friends across the pond: The Horrors.

This tune, "She's a New Thing," comes from their first long-player: Strange House. The animated video, which looks like some Nightmare on Elm Street version of A-Ha's Take On Me, is a nod to the scrawling art of frontman Faris Rotter. Long before he was the cadaverous frontman of The Horrors, Faris would compulsively fill Moleskine notebooks with intricate bizarre-o doodles (see above). Rotter's turned his manic drawings into a whole side project, having done fanzine covers and even a whole solo show at London gallery.

Here's The Horrors' "She's a New Thing." Warning: this video contains NSFW images of animated nipples. Though, to be fair, if you work in an office that would flip out over that, your office mates will find plenty of other WTF imagery in here to get upset about. By the time they've made a list, they might forget all about the nipples.

Enjoy!

This tune, "She's a New Thing," comes from their first long-player: Strange House. The animated video, which looks like some Nightmare on Elm Street version of A-Ha's Take On Me, is a nod to the scrawling art of frontman Faris Rotter. Long before he was the cadaverous frontman of The Horrors, Faris would compulsively fill Moleskine notebooks with intricate bizarre-o doodles (see above). Rotter's turned his manic drawings into a whole side project, having done fanzine covers and even a whole solo show at London gallery.

Here's The Horrors' "She's a New Thing." Warning: this video contains NSFW images of animated nipples. Though, to be fair, if you work in an office that would flip out over that, your office mates will find plenty of other WTF imagery in here to get upset about. By the time they've made a list, they might forget all about the nipples.

Enjoy!

Sunday, June 22, 2008

Comics: Better than "best."

Tagging your anthology "best of", whether it is a greatest hits CD or a genre-centric compilation or a cookbook, is always a losing proposition. At best, editors treat the label as a marketing burden and freely hone-up to how impossible it will be to live up to the implication. For what might rank as the very limit of editorial self-flagellation regarding the use of "best of," check out David Foster Wallace's self-deconstructing introduction to The Best American Essays 2007, a performance that would well rank as the finest parody of modern liberal academic intellectual paralysis if the reader could shake the notion that Wallace thinks this sort of masturbatory tail-chasing is actually the essence of insight.

Tagging your anthology "best of", whether it is a greatest hits CD or a genre-centric compilation or a cookbook, is always a losing proposition. At best, editors treat the label as a marketing burden and freely hone-up to how impossible it will be to live up to the implication. For what might rank as the very limit of editorial self-flagellation regarding the use of "best of," check out David Foster Wallace's self-deconstructing introduction to The Best American Essays 2007, a performance that would well rank as the finest parody of modern liberal academic intellectual paralysis if the reader could shake the notion that Wallace thinks this sort of masturbatory tail-chasing is actually the essence of insight. At worst, one gets the feeling that the editors knowingly devalue the word. Like "victim," its ever-cheapening modern usage invites abuse by the cynical. The exemplars in this category were the folks at Mammoth, who seemed to put out a doorstop-sized Best of Some Genre or Another every four days. I don't think you can have visited a mid- to large-sized bookstore and not have run into these things: Mammoth Books of Best New Horror, of Best British Mysteries, Best New Sci-Fi, Best New Erotica, and so on. I've worked my way through a couple of these anthos before and the results have always been mixed, with the scales slightly tipped in favor of disappointment. Consequently, when I saw that Mammoth was responsible for a line of comics-related "best of" anthologies, I did not hold high hopes.

Happily, the folks at Mammoth took advantage of my nonchalance to, ninja-style, sneak up on me and kick my ass.

The first of the "best of" comic anthos I picked up was The Mammoth Book of Best War Comics. Read the Amazon reviews of this 500+ page brick of comic goodness and you'll find a common theme: "This isn't the best of! Where's Sgt. Rock? Where's Haunted Tank? Ye Gods! What are you trying to pull here mine editor Mammothy?" This is, I guess, fair. The book is not a collection of fan faves. I suspect that economic played a part in this. What with success of the phonebook-sized Showcase editions converting the back catalog of the Big Two in a surprisingly productive gold mine, near forgotten war comics are suddenly valued properties. More than the capitalist illogic of property right, however, the real reason for the lack of the usual suspects is that the editor of War Comics did something mo' better than a re-run of shop-worn classics. David Kendall produced an anthology meant to not only showcase some of the best comic art about the theme of combat, but to expand the very notion of what war comic was. This is one anthology features manga about the dropping of the atomic bomb, gung-ho post-World War II Brit heroic "realism," '60s underground surrealism abut 'Nam, a fantastically weird children's tale about the Falklands conflict, nightmares about wars still to come, and more. There are acknowledged masterworks, such as Eisner's Last Days in Vietnam and Mill's and Colquhoun's unbelievable Charley's War (perhaps the single greatest comic art statement about men in combat), and surprising choices, such as the Russian artist Askold Akishin and Sweden's Fabian Goranson. Critics who bitch about the lack of The Unknown Soldier are right about the antho for all the wrong reasons. They're like movie-goers who stumble out of Apocalypse Now complaining that it was no The Green Berets. There are some real problems with the Mammoth book. Some of the reprinting is atrocious and seeing some of the fine art so muddied is a distracting frustration. There's also a seemingly random selection of color plates that actually cut out before one of the color stories ends. What's going on there? The cover's pretty cheesy too. That's not so good. Still, in terms of selection, the Mammoth anthology represents not just a solid look at war comics, but a significant contribution to comic's history and appreciation. If I was the Mayor of Comic Business Town, serious fans of the medium would have found War Comics on their required reading list.

Which brings us, Screamers and Screamette's, to The Mammoth Book of Best Horror Comics a 500+ page doorstop that has the unenviable task of following on the heels of its more martial sister-tome. Is Best Horror Comics another triumph?

The Mammoth Book of Best Horror Comics is not the essential volume the War Comics is; but it a success on its own terms. Partially, this distinction between the two volumes has to do with a shift in editorial focus. Instead of trying to bush the boundaries of what constitutes the genre, Best Horror makes and effort to establish the long and unbroken history of the horror comic, making an argument for its status as crucial comic genre, perhaps second only to the enduring superhero genre. With this more narrow focus, readers are not going to have their notions of the genre transformed. But they will get a interesting, if necessarily incomplete, tour of the history of scare stories in the comic rags.

MBHC will start with a surprise selection for many comic fans. Editor Peter Normanton begins his historical overview nearly a full decade before the '50s boom most of us identify as horror comic's Big Bang. In the war years, anthology comics would plunder well-known short stories for ready material. In the case of 1944's "Famous Tale of Terror," from Yellowjacket Comics, it's Poe's "The Black Cat" that gets the comics treatment. From this interesting start, the book divides horror comics into four broad periods: a golden age in the 1950s, a revival period in the 1960s and 1970s, a period of decline in the '80s and '90s, followed by a second revival in the early 21st century.

Unsurprisingly, the first two sections are the strongest. These are widely admitted to be the golden and silver ages of horror comics. In fact, just the look of these works is so synonymous with "horror comics" that almost anything you chose is going to feel iconic. Not that the editor takes advantage of this to phone it in. The selections from the first two great periods of comic horror are consistently solid, often great. Regular readers of LoTT-D member blog The Horrors of It All will recognize some the material from the '50s. Fans will recognize the talent of luminaries like Jack Cole, Don Heck, Rudy Palais, Jack Katz, and Jerry Iger.

The selections from the last two periods are more spotty. This is almost necessarily so, as the premise of the last two periods is that horror entered an era of slim-pickings and that the new era has just started up. In the former case, you take what you can get. In the latter, nothing's yet attained the critical patina of "classic" yet. Still, even if we grant those difficulties, it is only in these later sections that we start to get some duds. Most notably a couple of stories that rely on photomontage techniques or drawn-over photos to create their visuals. Though these techniques were popular throughout the 60s and 70s in some Mexican comics, they have never really caught on in the US. I have a complex and nuanced theory as to why this is. My theory goes like this: it looks like crap, that's why. The talent in these later sections includes Steve Niles, Mike Ploog, and Arthur Suydam.

Best Horror dumps the whole color plate thing – which is fine with me considering that they were somewhat wasted in Best War. Though there are some problems with the quality of the reprints, I think Best Horror is an improvement over the previous collection. Scholars and hard-core fans will want to seek out the originals, of course, but more casual fans and first time readers wouldn't find themselves distracted by QC problems.

While less ambitious than Best War Comics, Best Horror is, in its own way, no less successful. Fans of horror comics have had histories and overviews to read before (notably Sennitt's Ghastly Horror), but this is the first comic anthology that covers the same ground. People will always quibble about what should have made the cut. It comes with the territory when you slap "best" on anything. But that's nitpicking. The real goal of "best" isn't to establish a canon or showcase new and hot writers. Instead, it sets a timeline for the development and evolution of horror comics and makes a case for the genre's enduring importance. Great and ghastly stuff.

The Mammoth Book of Best Horror Comics is published by Running Press and it is going to set you back about 18 clams. It's out now.

Friday, June 20, 2008

LoTT-D: The Hungarian Suicide Song, but in blog form.

The League of Tana Tea Drinkers welcomes the genius behind Gloomy Sunday to their ranks. Posting under her nom de blog Absinthe, GS's mistress of ceremonies specializes in Gothic romance novels, from the seminal classics like Radcliff's The Mysteries of Udolpho to more obscure finds from the golden age of the mass market paperback. With her entertaining reviews, she posts boss cover images. Viewers who dig the pop goodness of Groovy Age might find GS another great source for cover art that tickles their fancy. Along the way Abby drops in some movies, opines, and otherwise comports herself in a manner befitting a blogger of note. Do check it out, won't you.

The League of Tana Tea Drinkers welcomes the genius behind Gloomy Sunday to their ranks. Posting under her nom de blog Absinthe, GS's mistress of ceremonies specializes in Gothic romance novels, from the seminal classics like Radcliff's The Mysteries of Udolpho to more obscure finds from the golden age of the mass market paperback. With her entertaining reviews, she posts boss cover images. Viewers who dig the pop goodness of Groovy Age might find GS another great source for cover art that tickles their fancy. Along the way Abby drops in some movies, opines, and otherwise comports herself in a manner befitting a blogger of note. Do check it out, won't you.Which reminds me . . .

Here's a Instructable on how to make a version of absinthe - the drink, not the blogger.

Thursday, June 19, 2008

Stuff: Stuffed.

Custom Creatures Taxidermy, itself a creation of artist Sarina Brewer, will not only whip together a stuffed creature that previously existed only in your head, see the gaff (an old carny term for a faked-up beastie) shown above, but they can also provide you with preserved chupacabras, stuffed unicorns, mummified werewolf hands (or is it paws?), and other uncanny artworks.

My wife would most likely kill me - and then have me stuffed - if I brought one of these amazing pieces into our humble home. But that's shouldn't stop you from throwing a little biz CCT's way. For the truly show-stopping pieces, check out the "carcass art" category.

Labels:

chupacabra,

custom creatures taxidermy,

Stuff,

werewolf

Tuesday, June 17, 2008

R.I.P.: The other Stan the Man.

I don't have anything really important to add to the greatly deserved praise pouring out of the Internet for the late Stan Winston. Obits in all-pro outlets like the NYTimes and fan tributes, like the fond farewells at Arbogast on Film and Final Girl, among others, will tell you all you need know about his long and enviable career.

I don't have anything really important to add to the greatly deserved praise pouring out of the Internet for the late Stan Winston. Obits in all-pro outlets like the NYTimes and fan tributes, like the fond farewells at Arbogast on Film and Final Girl, among others, will tell you all you need know about his long and enviable career.With your indulgence, I would like the chance to throw in a personal memory. When I was a little kid, I only read two kinds of books. One of them was a trade paperback (though this was well before such collections were the industry norm) of superhero team-ups in the Mighty Marvel Manner. I read that over and over until the front cover fell off, the spine broke, and I lost a couple pages of a titanic struggle between Thor and the Silver Surfer – a battle I remember taking place in, of all places, Thor's dining room.

The only other printed pages that could hold my interest were in non-fiction books about dinosaurs. I was pretty young, so we're talking about pretty basic stuff here. Mostly these books had some cool pictures of fighting dinos. There was always the obligatory size-comparison picture: some child in clothes two decades too old standing next to various giant lizards. Usually the child and the dinosaurs were in a row, as if they were in some unimaginable police line-up: "Number 5, please approach the mirror and roar."

I never became a paleontologist or anything. I was interested in living, fighting dinosaurs. The idea of galumphing about the globe looking for fossilized remains seemed pretty lame by comparison. Perhaps I lacked the requisite imagination for it. Perhaps I simply don't possess a scientific mind. Anyhow: dino obsession was a crucial part of my childhood that remained strictly a childhood thing.

This connects to the career of Stan Winston, of course, through Jurassic Park. Winston did all the live-action dinosaurs for all three of flicks that currently make up the franchise. This includes the animatronic Spinosaur: a multi-story, 12-ton monster that holds the record for being the largest animatronic ever built.

I saw Jurassic Park in Washington D.C., on an enormous screen in a classic theater called the Uptown. It was opening night and the theater was packed. I remember the thrill that went down my spine when the first dinosaurs, a couple of grazing brontosaurs, appeared on the screen. I was instantly transported back to my youth when the only things I really cared about were comic book heroics and the lives of the long-dead thunder lizards. I was, for a couple of hours, a little boy again. Though I've seen the film several times since, as well as its sequels, I never get tired of the watching the dinosaurs.

Thanks Stan. You did good work.

Monday, June 16, 2008

Movies: Beyond the Valley of the Jolly Green Giant.

The Criterion Collection has a strangely schizo relationship to the horror genre. Horror flicks make up only a tiny percentage of the collection (it is handily beat by mystery/crime and sci-fi, but still towers over porn, which is represented by the I'm Curious box set and a couple stray "erotica" titles). What they do have tends to be separated into three general categories. The first consists of horror flicks that are genuine cinema milestones, the sorts of flicks that people tend to think of a singular achievements rather than reflections of a genre. Films like M and Peeping Tom go in this category. In the next category you get meta flicks that use the horror genre as little more than a steeping stone for staging their own art house provocations. Paul Morrissey's surreal black-comedy takes on Dracula and Frankenstein are emblematic of the flicks in this category. Finally, there's a tiny collection of cult whatsits that reside on the list. Carnival of Souls and The Blob are the most famous of these films, but this category includes such oddities as The Fiend Without a Face (a 1958 monster movie featuring an invasion by brain creatures with spinal-cord tails) and the subject of today's review: the 1967/1970 monster movie Equinox.

The Criterion Collection has a strangely schizo relationship to the horror genre. Horror flicks make up only a tiny percentage of the collection (it is handily beat by mystery/crime and sci-fi, but still towers over porn, which is represented by the I'm Curious box set and a couple stray "erotica" titles). What they do have tends to be separated into three general categories. The first consists of horror flicks that are genuine cinema milestones, the sorts of flicks that people tend to think of a singular achievements rather than reflections of a genre. Films like M and Peeping Tom go in this category. In the next category you get meta flicks that use the horror genre as little more than a steeping stone for staging their own art house provocations. Paul Morrissey's surreal black-comedy takes on Dracula and Frankenstein are emblematic of the flicks in this category. Finally, there's a tiny collection of cult whatsits that reside on the list. Carnival of Souls and The Blob are the most famous of these films, but this category includes such oddities as The Fiend Without a Face (a 1958 monster movie featuring an invasion by brain creatures with spinal-cord tails) and the subject of today's review: the 1967/1970 monster movie Equinox.What's interesting about this tripartite breakdown is that the flicks in the last category often seem to get the best treatment. M and Peeping Tom get nice transfers with the requisite commentaries and whatnot. They're quite spiffy. But, by way of comparison, Carnival of Souls gets a 2-disc box with a couple of hours worth of extra stuff. Arguably Carnival fully deserves the attention. It is truly one of those rare genre cheapies that completely deserves its worshipers. But even Equinox, probably one of the most obscure titles in the entire collection, gets a similar 2-disc rollout – including an alternate version of the flick, a wealth of production resources, and two short films: one animated flick and a sci-fi/horror monster short. Perhaps the makers and fans of these cult and sub-cult flicks simply keep more of the ephemera around, providing Criterion's people with unusually rich stores of potential special features. Maybe it is some sort of pre-emptive effort to head of criticism of including such weird flicks in the collection: by piling on extras and bonus stuff and whatnot, the sheer wealth of material acts as a sort of argument against the flick's irrelevance. It might simply be that the folks over at Criterion have a sincere soft spot for these often clunky but usually charming films. I don't know. But, whatever the reason, these film curiosities are frequently given the royal treatment.

Does Equinox deserve the deluxe treatment?

Equinox began life in 1967 as a sci-fi/horror short cobbled together by first time-director and then full-time business student Dennis Muren. Muren shot the film on a shoe-string budget of $6,500 dollars. The short was picked up by a distribution company that hired new talent to shot new material that would pad out the flick to feature length. In 1970, the longer, re-organized film was released onto the drive-in circuit. Muren would go on to do effects for an astounding number of flicks, many of them considered major turning points in the history of film effects, including Star Wars, E.T, Raiders of the Lost Ark, The Abyss, Terminator II, and Jurassic Park. Horror scuttlebutt claims the flick went on to become an influence on the gents behind Evil Dead, with which it shares certain plot points and a goofy, slightly mad DYI attitude.

Though the shorter, original flick is available in the 2-disc set, we'll discuss the longer theatrical release. The film begins with a bang, literally: an unexplained explosion fills the screen, throwing an unnamed young man to the ground. He gets up and begins calling for his friend. We soon see her body, immobile and covered in blood, not far from him. Deciding his friend has died, the young man makes a panicked dash for the nearest highway. Once there, he tries to flag down a car. Unfortunately for him, the first car to come by is an empty sedan being steered by some unseen force. The driverless auto rams the young man, leaving him injured in the middle of the road.

One year later, a reporter comes to see the young man in a mental asylum. The head of the hospital's department of exposition tells us that the young man was found by motorists and brought in for care. They treated his physical injuries, but he was hopelessly loony by that point. He raved on about forces of evil and refused to surrender a small crucifix that was found on him. The reporter tries to speak to the young man, but the man attacks him. The doctor, apologizing for the patient, shares a recorded interview he had with the young when he was first brought in. Cue extended flashback.

The young man, David, his blind date Susan, his buddy Jim (an early role for WKRP's Frank Bonner), and Jim's girl Vicki all head into the California hills for a picnic and meet-up with Dr. Waterman. Waterman, according to David, has made some sort of mysterious find in the hills. Our quartet arrive to find Waterman's cabin completely demolished and, shortly thereafter, is given a mysterious book by a crazed local. The book turns out to be a Bible of Evil (basically the Necronomicon; though it is never so named) which Waterman was studying. From some research notes, the four friends learn that Waterman summoned monsters that he couldn't then control. What follows is the single worst picnic to ever be put to film as the foursome battle giant stop animation monsters, a guy who looks like a cross between Captain Caveman and the Jolly Green Giant, and Satan himself, who is skulking around California's state parks in the guise of thuggish park ranger. Before the battle is through, Satan's powers will have turned friend against friend. Though we know that only David makes it out of the woods from the exposition in the hospital, it is still bizarrely effecting when this otherwise goofy fantasy film actually starts dispatching characters.

There's no good explanation for the inexplicable watchability of Equinox. The effects, while good for a budget of less than seven grand, are still mighty laughable. The story is loopy, full of distracting plot holes, and very uneven in tone – the grim fate of several of the characters works against the fun feel of the earlier parts of the flick and seems like overkill. The acting is wooden and unconvincing. Plus, the couple of Jim and Vicki are perhaps the least pleasant screen couple I've witnessed in a while. Jim snipes at Vicki so regularly that you almost expect him to just start saying things like, "Dammit. Are you still here, Fatty? I was hoping that giant demon bat thing ate you."

Still, there is something weirdly compulsive about this flick. Despite these flaws, it is clear that this flick is the work of inspired, talented amateurs giving something everything they've got. The actors are not equal to their parts, but they are always game. The effects are extremely lo-fi, but the monster designs and psychedelic visual effects have a kitbashed coolness that is disarming. The pleasures Equinox delivers are real, if remarkably specific and limited. It's like being surprised by the inventiveness of some friend's homemade flick (if your friend went on to make some of the biggest effect flicks of all time). There's something completely garage rock about Equinox. It speaks to the fantastic notion that simply by loving something enough to give a crap about it, you could do it yourself. The fan could just pick up the guitar. The kids watching the late night creature features could pick up a camera and just make one. That this fantasy is never as easy as it sounds doesn't detract from the essential core of what makes it so attractive: we know it is true.

Does that deserve a 2-disc extravaganza? I say sure. Why the hell not? If that isn't worth celebrating, then I don't know what is.

Saturday, June 14, 2008

Music: 'Cause even monsters deserve access to good health care.

Though supported by a rotating crew of other staff members, the core of the Canadian indie rock outfit Metric is the duo of Emily Haines and James Shaw (also of Broken Social Scene fame). The video for the New Wave revivalist's 2005 "Monster Hospital" starts with a Ghostbusters kidnapping-of-the-gatekeeper/Repulsion reference but develops a bizarre and freaky Jacob's Ladder feel to it.

Sadly, I cannot embed the video because the Universal Music Group has made the wise decision to disallow the easy and wide dissemination of otherwise free two-year-old music video. Good thinking, gentlemen. That'll hit those pirates in the sensitive bits.

Anyway, click this very link and be magically transported to the video in question:

Angular riffs and stage blood: enjoy!

Sadly, I cannot embed the video because the Universal Music Group has made the wise decision to disallow the easy and wide dissemination of otherwise free two-year-old music video. Good thinking, gentlemen. That'll hit those pirates in the sensitive bits.

Anyway, click this very link and be magically transported to the video in question:

Angular riffs and stage blood: enjoy!

Friday, June 13, 2008

Movies: Got woods?

That the ironically named Lucky McKee continues to be widely ignored and relegated to cult status says more about the fundamental state of contemporary horror than any amount of critical fuss about the supposedly negative impact of torture porn or the hopeful box office numbers for flicks like The Strangers. McKee's films are smart, effective, stylish, wonderfully-built works that neither pander to low audience expectations nor wallow in self-indulgent genre hipsterism. McKee's films emerge from a rich background of horror allusions, but they never fail to be original and always bear the unique signature of his dead-pan magical realism. The Woods, McKee's 2006 feature about a witch possessed 1960s girl's school, shows the director at the top of his form.

That the ironically named Lucky McKee continues to be widely ignored and relegated to cult status says more about the fundamental state of contemporary horror than any amount of critical fuss about the supposedly negative impact of torture porn or the hopeful box office numbers for flicks like The Strangers. McKee's films are smart, effective, stylish, wonderfully-built works that neither pander to low audience expectations nor wallow in self-indulgent genre hipsterism. McKee's films emerge from a rich background of horror allusions, but they never fail to be original and always bear the unique signature of his dead-pan magical realism. The Woods, McKee's 2006 feature about a witch possessed 1960s girl's school, shows the director at the top of his form.Superficially, the plot of The Woods sounds like a rip-off of Argento's classic Susperia. In the late 1960s, a young girl, the rebellious Heather, is deposited at an elite girl's school by her egomaniacal, overbearing mother and milquetoast father (played by horror icon Bruce Campbell). Once there, Heather immediately runs afoul of the Mean Girls grade alpha-female click. But these socially-predatory teens are the least of Heather's problems. The headmistress, Ms. Traverse (played Oscar-nominated and multi-Emmy winner Patricia Clarkson), and the school's staff are hiding a dark secret. As students disappear and inexplicable incidents pile-up, Heather uncovers a sinister coven of witches whose evil plans threaten the lives of all the students at the academy.

It would be easy to dismiss The Woods as little more than "an American Susperia." And, in a way, that's exactly what it is. In his previous film, 2002's May, McKee revealed his love of Italian horror by not only name dropping Argento's Opera and Trauma, but also by working in some of said directors more dreamy stylistic ticks into the later sequences dramatizing the title-character's violent descent into madness. It is, I think, unlikely that McKee wasn't fully aware of Argento's legendary flick. However, The Woods is no remake or exercise in slavish stylistic imitation. If you're going to think of this as the American Susperia, then you need to imagine that McKee tore the film down to its most basic core and rebuilt it with distinctly American elements. Stylistically, McKee looks to the sun-drenched retro look of the nostalgia industry: colors are crisp, all cars have a factory-fresh shine to them, the period details are exacting but comfortable. Think Stand By Me or The Wonder Years. The elements of fantasy are shot with surrealistic stagy, crispness – the fake-real of Hollywood sets when make-up, costume, and art design were your chief special effects. Even the one CGI effect of note, the movement of Ruins-like vines and branches, has a solid, carefully-studied quality.

The plotting and characterization also stand in contrast to the dream-logic minimalism of Argento's work. The story feels like a Nancy Drew mystery as imagined by Ray Bradbury. The mystery is genuinely unfolded, rather than simply distilled by the director and screenwriter. The supernatural elements are sinister and magical, but not nonsensical and deployed willy-nilly whenever a scare is needed. The actors all turn in effective work, partially because McKee gives them space to tweak what could be otherwise stock roles. In fact, McKee might be one of the few horror directors who is not, if feel, in any way sadistic. This is not to say there isn't violence and gore (though The Woods has much less than May and May had much less than your standard slasher fare), but that McKee isn't simply interested in them as fuel for whatever cruel scheme he's cooked up. They suffer because horror demands danger, but McKee is more interested in what they'll do than what he can do to them.

There's something about The Woods that harkens back to an age when the horror film was not yet a cinematic ghetto. It reminds me of Robert Wise's The Haunting or the stylish thrillers Val Lewton produced. The resemblance is not in visual style or content elements, but in a common approach to high-quality genre filmmaking. There's a professional storyteller's care in how Wise, Tourneur, and McKee approach their stories. They follow through on their plots; they use violence as a dramatic tool rather than an emotional smoke screen; they create characters they care about in hopes that you will too; though they respect mystery, they don't leave things hopelessly obscure knowing that forgiving fans will conspire to confuse sloppy work for stylish intelligence; they appeal to lovers of good stories, not to genre otaku who demand fanservice. This isn't to say that McKee is a throwback or some postmodern recycling specialist who is lucky to have inadvertently picked up some good habits by virtue of stealing from his betters. Technically and thematically McKee's skills, style, and concerns are thoroughly up-to-date. What McKee is an example of is even rarer than that: he's a guy committed to good filmmaking. It is his unfortunate luck to arrive on the scene when the worship of trash cinema, pursuit of vacuous visual extremism, elevation of obscurantism, and genre fundamentalism appear to rule the day.

Thursday, June 12, 2008

Stuff: Hack and slash.

My friend and ANTSS regular Screamin' Dave over at Forbes's Digital Download found this horror-related prank in the MIT online hack archive.

My friend and ANTSS regular Screamin' Dave over at Forbes's Digital Download found this horror-related prank in the MIT online hack archive.

Wednesday, June 11, 2008

LOTT-D: The kids are all fright!

The latest League of Tana Tea Drinkers Roundtable is up. The topic under discussion is "evil kids." From The Bad Seed to The Ring and all points in-between, league members opine on the terrifying tots that have been the pro-choice movement's greatest cinematic mascots. I'm a little sad to see that Milo, the titular homicidal demon child of the 1998 fright flick, didn't get a shout out. Still, you can't have everything, Screamers and Screamettes. Where would you put it all? Besides, the quality of the League's write-ups more than compensates for this otherwise unforgivable oversight. Check it out.

The latest League of Tana Tea Drinkers Roundtable is up. The topic under discussion is "evil kids." From The Bad Seed to The Ring and all points in-between, league members opine on the terrifying tots that have been the pro-choice movement's greatest cinematic mascots. I'm a little sad to see that Milo, the titular homicidal demon child of the 1998 fright flick, didn't get a shout out. Still, you can't have everything, Screamers and Screamettes. Where would you put it all? Besides, the quality of the League's write-ups more than compensates for this otherwise unforgivable oversight. Check it out.Vault of Horror discusses why the destruction of childhood, both literally and metaphorically, remains horror's biggest and most strangely attractive taboo.

Kindertrauma, our resident specialist on all things small and creepy, discusses the two major categories of evil child and the impact they have on us.

Gospel of the Living Dead focuses in on zombie children.

Blogue Macabre takes a close look at how evil children play to our conscious and unconscious anxieties.

TheoFantastique looks at the political implications of a classic "evil child" episode of The Twilight Zone.

And, last but not least:

Unspeakable Horror gets a little Freudian on us and discusses how he's used the concept of the "evil child" in his comic book work.

If you're anything like your humble horror host, then you didn't need another reason to hate children. But, better safe than sorry, right?

Tuesday, June 10, 2008

Movies: Is everybody in? Is everybody in?

Inside, the co-directing debut of Alexandre Bustillo and Julien Maury, is one of the latest flicks in a small but steady stream of bloody French imports. It takes a plot of primal simplicity – one attacker, one victim – and turns it into a stylish, meticulous, energetic, and gore-soaked struggle that initially galvanizes the viewer only to, in the end, leave them feeling utterly exhausted.

Inside, the co-directing debut of Alexandre Bustillo and Julien Maury, is one of the latest flicks in a small but steady stream of bloody French imports. It takes a plot of primal simplicity – one attacker, one victim – and turns it into a stylish, meticulous, energetic, and gore-soaked struggle that initially galvanizes the viewer only to, in the end, leave them feeling utterly exhausted.Setting against the backdrop of the 2005 immigration riots in the outskirts of Paris, Inside tells the story of Sarah, a pregnant photojournalist who, after losing her baby's daddy in an auto accident that nearly took the unborn child and left her physically scarred, is spending Christmas alone. Christmas night an unnamed woman busts into Sarah's home. Her goal, we quickly learn, is to cut the baby out of Sarah's womb. Think of it as a violent, unilateral form of adoption. (As contrived as this sounds, there have been at least three recorded real-life cases in which crazed would-be mothers have attempted amateur-Cesarean kidnappings.) What follows is a long, brutal night in which Sarah, trapped in a bathroom on the second floor of her home, tries repeated to escape her attacker. This grim stand-off is violently punctuated by the arrival of various relatives, friends, and police officers, all of whom will face-off against the anonymous attacker.

The two key roles are ably played, but somewhat thankless. The fragile beauty of Alysson Paradis makes the lead role of Sarah an effective center to viewer concern, but she's supposed to play an emotional shut-in so there is a real limit to how deeply we can connect with her. Her attacker is played by the truly fascinating Béatrice Dalle, a controversial art house fixture on the French film scene. In real life, Dalle's explosive personality (she attacked a French police woman over a parking violation) and bizarre love life (she was secretly married to unnamed prisoner at a prison she was doing volunteer work in) are the stuff of tabloid dreams. Cinematically, she taken projects that fit her odd profile – including the horrible Trouble Every Day, the worst film this blogger has ever had to sit through. Dalle's oddly captivating looks and hot-and-cold acting style make for an unusually interesting villain. She slides between killing-machine and pathetic-loony with ease, playing with audience expectations. She is also the most stylish slasher in recent memory: she goes to work in a floor length black gown and leather opera gloves.

Like High Tension, the violence of Inside is extreme. In the "making of" featurette for the former flick, the director claimed that French cinema culture was inherently adverse to extreme violence. They are, he opined, lovers, not fighters. The recent spate of bleak and brutal French drama and horror films (Irreversible, Kiss Me, Frontier(s), High Tension, and Inside) would suggest that this is no longer the case. Inside takes practically revels the display of the mushy, fluid details of human existence. Aside from the gallons of blood that the directors practically paint the house with, we're treated to scenes of vomit, tears and snot, and urine. Though the violence isn't particularly realistic – the capacity of these characters to absorb damage and continue struggling stretches disbelief and very nearly tips over into some dark form of slapstick – it is considerably more effecting and graphic that anything I've seen in recent memory.

Set against the unhinged relish with which the filmmakers show gore and violence is the polish of their visual approach and an oddly elegant series of structural binaries used to give the film a thematic and visual template. Like many contemporary horror films, Inside makes full use of DV technology to escape the visual restrictions of its relatively small budget. It has the slick, professional look of films like Hard Candy, Saw, and Hostel. However, unlike those films, Inside borrows occasionally from French New Wave techniques, working in jump cuts and intrusive camera tricks that break the viewers disbelief while adding to the emotional unsettled feel of the picture. The technical proficiency of the filmmakers in and of itself is unsurprising: this slick look is the visual lingua franca of modern horror. What is notable is the overt structuralism of the flick. Our heroine dresses in white, the villain in black. In the flashbacks to the car wreck, which becomes a sort of origin story for both women, the cars are white and black (Sarah's car is actually silver, but it is shot with a glare on it, making it appear white). There are repeated inside/outside motifs. Sarah's trapped in the white title bathroom while her swart-clad assailant lurks in the darkened hall outside. This plays out again and again with the folks who come to the house and then jumps to a different scale when the theme of native versus immigrant conflict is overtly introduced. Like the main characters, rooms in the house end up getting color-coded: the bathroom is white, the upstairs bedroom is blue, the living room is orange, the kitchen is yellow. This is by far the best manically blood-soaked slasher flick that Peter Greenaway never made.

(A comparison of the French film poster, above, and the American DVD cover, below, is interesting. The French poster not only has a curiously – ironic? – patriotic color-scheme, it emphasizes the structuralist bent of the flick: up/down, left/right, blue/red. In contrast, the American box art emphasizes the gore. The blood that is a disembodied design element or abstracted body paint in the French poster gets slathered over a preggers tummy. The Woman in Black's favorite weapon, a pair of scissors, hovers hungrily above the mommy-flesh.)

Curiously, the interplay of all these themes never materializes into a "message." Inside, despite playing with the concepts of motherhood, security, immigration, and violence, does not venture any socio-political theories. It doesn't pretend to offer up insights into the nature of cruelty or reach to attempt to create a metaphor for the sort of fierce maternal instinct (like, say, the final act of Aliens did). I've seen some reviewers criticize the film for groping towards, but failing to achieve any important deeper meaning. I suspect that feeling is a result of these repeated, organizational binaries. We feel that they should communicate something. We're attuned to think of any patterns we find in that way. But, honestly, these tropes are really just surface elements that ground the work visually and serve to keep us fully engaged despite the natural reaction to simply tune out the violence. It is a neurological bait and switch that forces the reader to minutely examine the unjustifiable, to probe the ultimately mute violence for something to redeem it. The answer is, of course, that there is no redemption for what happens. Like the nameless attacker, the flick treats violence as a cipher that sweeps away everything before it. This is, depending on your point of view, either a massive cop-out on the part of the filmmaker or the only genuinely moral way to view violence. While I personally lean towards the later, I sympathize with those who find it a crass and exploitative abdication of the duty of the artist. Nihilism always runs the risk of lapsing into a sort of immature naïveté that mistakes simple-minded extremism for the wisdom of moral certitude.

Whether or not the project fails on a moral or intellectual level, there are some artistic fumbles that mar the film. Like the plot of Texas Chainsaw Massacre, the plot of Inside can only keep moving forward if fresh bodies stumble into the home. When this first happens, it is genuinely intense. As a pattern, it is simply frustrating. The second problem, for me, has to do with the intensity and regularity of the violence. Eventually I was simply fatigued. Compared to Inside, Hostel and Saw are downright generous with the viewers' sensibilities. There came a point for me, about 15 minutes from the end of the flick, when I was simply unable to muster concern for any of the characters because it seemed so unlikely that any of them could possibly survive what had happened or, honestly, that any of them would want to given all they'd endured. I suspect this is part and parcel of the program of presenting violence as the opposite of the meaningful, as the point where you can no longer talk or wax philosophic and you can only feel. If so, it is philosophically a success, but the experience is something akin to an endurance test.

Did I like Inside? I'm not sure it is built to be liked, really. It is one of the most intense horror film experiences I've had in some time, and its emotional punch is not come by cheaply. But, at the same time, it is not a particularly thoughtful, meaningful, or important film. It is odd: what does one make of something so slight and yet so profoundly unnerving?

Monday, June 09, 2008

Meta: ANTSS becomes the Marvin of the horror-blogging Superfriends.

Today the fine folks over at The League of Tana Tea Drinkers invited your humble horror host to join the merry macabre band of malicious malcontents. I, cribbing a calm and collected response from James Joyce said, "Yes I said yes I will Yes."

Today the fine folks over at The League of Tana Tea Drinkers invited your humble horror host to join the merry macabre band of malicious malcontents. I, cribbing a calm and collected response from James Joyce said, "Yes I said yes I will Yes."So, Screamers and Screamettes, you might well ask, how will this meteoric, if entirely justifiable, rise to almost unimaginable Internet fame affect CRwM?

Well, in a rushed and utterly half-assed attempt to put the League logo on my sidebar, I completely wiped out all my links and had to scramble to fix my freakin' blog. I reckon that sort of regularly displayed incompetence should serve to keep me well grounded.

Sigh.

Still, it is an honor to be asked to join up. Please check out the new LOTT-D link in the recently un-destroyed sidebar and look for future ANTSS participation in League round-tables, guest shots, and other good stuff.

Friday, June 06, 2008

Stuff: The bravest movie critic in all of Washington D.C.

Today Washington Post staff critic Ann Hornaday turned in a dismissive review of the upcoming Mother of Tears, the last installment in Argento's nonsensical Mothers trilogy-cause-I-said-it-is, and Stuck, Stuart Gordon's grim satire of the Chante Jawan Mallard case (in which she hit a pedestrian with her car, got him stuck in her windshield, and left him to bleed out – true story, swear to God – took the poor guy more than two hours to die).

The fact that the wonderfully named Hornaday basically dumps on both movies as muddled and gory wastes of time doesn't surprise me or disappoint me. My interest in Gordon is almost entirely based on his status as the go-to cinematic interpreter of Lovecraft. As for Argento: he's so reliably uneven that it is entirely unsurprising to hear one of his flicks is a stilted, bloody mess. Being charitable, even Argento's best films walk a thin line between bizarre puzzle and pretentious disaster.

Hornaday says of both flicks:

So, dear readers, in front of you and the movie gods and everybody, I'm here to say: I don't get it. I don't get why, in "Mother of Tears," I'm supposed to find some kind of taboo thrill in watching a young woman being strangled by her own intestine. I don't get that Argento can write some of the most wooden dialogue and elicit some of the most risible performances to be seen in a movie (think "The Da Vinci Code" with an even more cockamamie mythology), but still get credit as some kind of auteur because of the ingenious weapon he creates to impale two eyeballs at once. I don't get why, in the course of a 40-year career, Argento can still find anything new in a shot of a slit throat and rivulets of burbling, viscous blood. (To the inevitable defense that Argento's work is simply camp, I would say that anything this aggressively hateful forfeits the right to be called camp. As Susan Sontag rightly observed, even camp at its most outlandish reveals some truth about the human condition.)

Compared to the myriad perversions on display in "Mother of Tears" (culminating in the film's star, Argento's daughter Asia, almost drowning in a sea of sewage and cadavers -- grazie, papa!), the degradations of the flesh in "Stuck" look almost endearingly modest. Inspired by a true story, the film stars Suvari as a nurse's aide who hits a homeless man (Rea) and leaves him for dead after he crashes through her windshield. Although Gordon clearly has something to say about poverty, class mobility and throwaway lives, whatever substance might have oozed through "Stuck" is quickly stanched, to let flow the blood, gore and attempts at erotic humor (a catfight between Suvari and a naked rival played for laughs). Admittedly, "Stuck" features only one eye-gouging, but like "Mother of Tears" it climaxes in a fiery Grand Guignol, its portrait of misery and moral indifference complete if not even slightly credible.

There are things to value in "Stuck," including the lead and supporting performances, and Gordon's taut thriller-like pacing. But, like "Mother of Tears," I don't get it. I don't get what fascinates Gordon and Argento -- both men in their 60s -- about thinking up new ways to inflict pain. I don't get what's "ingeniously nasty" about watching people suffer and die. I don't get the "gonzo artistry" of murdering a woman by way of a symbolic rape with a sword. I don't get why that's entertaining, edifying, endorsed by the cinematic canon or even remotely okay.

Let it all out, Hornaday. Tell us how you really feel.

Seriously though, I suspect that most of Hornaday's basic criticisms are dead-on. Gordon's been a reliable, but strictly workman-like horror director for a couple decades now and nothing in his filmography suggests he's got a profound cinematic Jonathan Swift hiding in him, straining to get out. As for Argento: the last movie of his I saw was a "mystery" whose plot hinged on the supposed fact that crows are an innately vengeful breed of bird that will hunt down and peck to death people who hurt crows. His movies are shambling hulks of stylistic absurdity. That's you thing or it isn't, but few folks deny it.

Here's what I hated about her review. From the opening section:

When you work as a movie critic, you learn very quickly which filmmakers are unassailable: Michelangelo Antonioni, Ingmar Bergman and anyone associated with the French new wave are geniuses. Period. They're bulletproof, and to take a shot at them, whether by way of their body of work or an individual film, is to invite not just immediate derision but excommunication from the ranks of Approved Cinematic Authorities.

There's another version of this intellectual lockstep, one tier down from the universally acknowledged great masters, having to do with cult films by directors that nobody has heard of, other than those benighted souls who have spent their every waking hour in a sticky-floored repertory house. These are the films that over the past few years have often arrived in theaters "presented by" such reigning cinematic tastemakers as Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese; you can also find mention of them on such authoritative Web sites as GreenCine.com and in the hilariously on-point "The Film Snob's Dictionary" by David Kamp and Lawrence Levi.

Two films that coincidentally open today at the E Street Cinema come from directors with creditable standing in the annals of film snobbery: Stuart Gordon, whose film "Stuck" stars Mena Suvari and Stephen Rea, and Dario Argento, whose "Mother of Tears: The Third Mother" completes a trilogy he began in 1977. Gordon attained cult status in 1985 with the highly regarded "Re-Animator," an adaptation of a H.P. Lovecraft story. Argento helped create an entire film sub-industry in his native Italy known as giallo. Both filmmakers traffic in the kind of graphic horror made profitable by such franchises as "Saw" and "Hostel" but enjoy pride of place, along with zombie auteur George A. Romero, as originators of the cult-horror form.

Because Gordon and especially Argento possess such cinematic cred, any self-respecting critic should greet the arrival of "Stuck" and "Mother of Tears" with the requisite phrases about dark humor, recurring visual tropes and pulp sensibilities. The tone should be ironic and supremely knowing: If, dear reader, you can't hang with the kind of graphic gore, sadistic violence, protracted torture and perverse sexist subtext that run through these movies, then you're obviously not in on the joke. You're a philistine. File under "Square, hopeless."

Hornaday, however, bravely resists falling into "intellectual lockstep." She tells those snooty film snobs where they can stick their cult directors. And she does it boldly, with no regard for what it will do to her career. Damn the consequences, she can see these particular emperors have no clothes and she's got the guts to call it like it is.

Why do I hate this? Because it is absurd self-aggrandizement based on half-truths, misunderstandings, and dismissive stereotypes, the final result being that it turns her lack of interest or knowledge about certain genres or filmmakers into a positive good rather than a gap in expertise.

First, let's look at her characterization of Gordon. Sure, I like him enough, but does he really occupy "pride of place, along with zombie auteur George A. Romero, as originators of the cult-horror form"? Stuart arrived on the scene nearly two decades after Night of the Living Dead. The number of directors and movies that arrived in the 20 years between those two flicks, all of which have a much greater claim for being "originators of the cult-horror form" than Gordon. Even among horror fans Gordon's a bit of a one-hit wonder.

As for Argento, perhaps I'm not self-respecting, but I haven't been booted out of the horror blog-o-sphere for thinking Argento's overrated. Maybe the jackbooted film taste police just haven't reached me yet. Or, and I know this sounds crazy, there's simply no goose-stepping central authority of horror fandom. Wait, wait: hear me out. Maybe, just maybe, horror fans are a pretty diverse group of people with varied tastes. Maybe we all apply slightly different critical criteria to the films we enjoy. We engage in dialog with other fans about relative merits. Sometimes we even respect one another's different opinions (not on the Internet, of course, but elsewhere it can happen).

But, then again, I'm not one of those who have spent my entire life in a "sticky-floored repertory house" (shades of the porn theater, that bit), so how I even know about the unbelievably obscure directors is a mystery. In the era of Netflix and the Internet, her characterization of the cult film world is a bizarre fantasy, not unlike the imaginary hordes of socially-stunted troglodyte basement-dwelling bloggers that mainstream literary critics fear are battering down the establishment's draw bridge.

Claiming outsider status is the last refuge of the intellectual bigot. When you can't make a good argument for defending your limited criteria for what makes a good work of art (and we all, by the nature that we don't have infinite capacities for appreciation, have limited criteria), you instead suggest that the issue at hand is that a cabal of elites have foisted what you don't like on you. Genre guys pretend that they've been marginalized by an evil conspiracy of elitist critics. Critics play the same game, simply reversing the positions to become the embattled defenders of true quality. Both sides appeal to the sadly innate American distrust of expertise and love of claiming the status of the righteous victim. You're a victim, fighting for truth and justice. This isn't about the fact that your tastes, knowledge base, and experiences might be ill-suited for the rigorous evaluation of these films. Rather, this is about how you, alone out of all your cynical and mean-spirited film critic ilk, had the mad courage to take a stand. This is what we do with our unexamined prejudices: we dress them up in the shoddy borrowed stage-finery of the "last honest man."

We salute you Ann Hornaday. You're so brave. When the collective weight of the film criticism world crashes down on you for your brave, so very very brave, refusal to toe the line, rest assured that you've got an open invite to guest blog here. Together maybe we can hold our against those barbaric hordes of, shudder to think, cult film fans.

The fact that the wonderfully named Hornaday basically dumps on both movies as muddled and gory wastes of time doesn't surprise me or disappoint me. My interest in Gordon is almost entirely based on his status as the go-to cinematic interpreter of Lovecraft. As for Argento: he's so reliably uneven that it is entirely unsurprising to hear one of his flicks is a stilted, bloody mess. Being charitable, even Argento's best films walk a thin line between bizarre puzzle and pretentious disaster.

Hornaday says of both flicks:

So, dear readers, in front of you and the movie gods and everybody, I'm here to say: I don't get it. I don't get why, in "Mother of Tears," I'm supposed to find some kind of taboo thrill in watching a young woman being strangled by her own intestine. I don't get that Argento can write some of the most wooden dialogue and elicit some of the most risible performances to be seen in a movie (think "The Da Vinci Code" with an even more cockamamie mythology), but still get credit as some kind of auteur because of the ingenious weapon he creates to impale two eyeballs at once. I don't get why, in the course of a 40-year career, Argento can still find anything new in a shot of a slit throat and rivulets of burbling, viscous blood. (To the inevitable defense that Argento's work is simply camp, I would say that anything this aggressively hateful forfeits the right to be called camp. As Susan Sontag rightly observed, even camp at its most outlandish reveals some truth about the human condition.)

Compared to the myriad perversions on display in "Mother of Tears" (culminating in the film's star, Argento's daughter Asia, almost drowning in a sea of sewage and cadavers -- grazie, papa!), the degradations of the flesh in "Stuck" look almost endearingly modest. Inspired by a true story, the film stars Suvari as a nurse's aide who hits a homeless man (Rea) and leaves him for dead after he crashes through her windshield. Although Gordon clearly has something to say about poverty, class mobility and throwaway lives, whatever substance might have oozed through "Stuck" is quickly stanched, to let flow the blood, gore and attempts at erotic humor (a catfight between Suvari and a naked rival played for laughs). Admittedly, "Stuck" features only one eye-gouging, but like "Mother of Tears" it climaxes in a fiery Grand Guignol, its portrait of misery and moral indifference complete if not even slightly credible.

There are things to value in "Stuck," including the lead and supporting performances, and Gordon's taut thriller-like pacing. But, like "Mother of Tears," I don't get it. I don't get what fascinates Gordon and Argento -- both men in their 60s -- about thinking up new ways to inflict pain. I don't get what's "ingeniously nasty" about watching people suffer and die. I don't get the "gonzo artistry" of murdering a woman by way of a symbolic rape with a sword. I don't get why that's entertaining, edifying, endorsed by the cinematic canon or even remotely okay.

Let it all out, Hornaday. Tell us how you really feel.

Seriously though, I suspect that most of Hornaday's basic criticisms are dead-on. Gordon's been a reliable, but strictly workman-like horror director for a couple decades now and nothing in his filmography suggests he's got a profound cinematic Jonathan Swift hiding in him, straining to get out. As for Argento: the last movie of his I saw was a "mystery" whose plot hinged on the supposed fact that crows are an innately vengeful breed of bird that will hunt down and peck to death people who hurt crows. His movies are shambling hulks of stylistic absurdity. That's you thing or it isn't, but few folks deny it.

Here's what I hated about her review. From the opening section:

When you work as a movie critic, you learn very quickly which filmmakers are unassailable: Michelangelo Antonioni, Ingmar Bergman and anyone associated with the French new wave are geniuses. Period. They're bulletproof, and to take a shot at them, whether by way of their body of work or an individual film, is to invite not just immediate derision but excommunication from the ranks of Approved Cinematic Authorities.

There's another version of this intellectual lockstep, one tier down from the universally acknowledged great masters, having to do with cult films by directors that nobody has heard of, other than those benighted souls who have spent their every waking hour in a sticky-floored repertory house. These are the films that over the past few years have often arrived in theaters "presented by" such reigning cinematic tastemakers as Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese; you can also find mention of them on such authoritative Web sites as GreenCine.com and in the hilariously on-point "The Film Snob's Dictionary" by David Kamp and Lawrence Levi.

Two films that coincidentally open today at the E Street Cinema come from directors with creditable standing in the annals of film snobbery: Stuart Gordon, whose film "Stuck" stars Mena Suvari and Stephen Rea, and Dario Argento, whose "Mother of Tears: The Third Mother" completes a trilogy he began in 1977. Gordon attained cult status in 1985 with the highly regarded "Re-Animator," an adaptation of a H.P. Lovecraft story. Argento helped create an entire film sub-industry in his native Italy known as giallo. Both filmmakers traffic in the kind of graphic horror made profitable by such franchises as "Saw" and "Hostel" but enjoy pride of place, along with zombie auteur George A. Romero, as originators of the cult-horror form.

Because Gordon and especially Argento possess such cinematic cred, any self-respecting critic should greet the arrival of "Stuck" and "Mother of Tears" with the requisite phrases about dark humor, recurring visual tropes and pulp sensibilities. The tone should be ironic and supremely knowing: If, dear reader, you can't hang with the kind of graphic gore, sadistic violence, protracted torture and perverse sexist subtext that run through these movies, then you're obviously not in on the joke. You're a philistine. File under "Square, hopeless."

Hornaday, however, bravely resists falling into "intellectual lockstep." She tells those snooty film snobs where they can stick their cult directors. And she does it boldly, with no regard for what it will do to her career. Damn the consequences, she can see these particular emperors have no clothes and she's got the guts to call it like it is.

Why do I hate this? Because it is absurd self-aggrandizement based on half-truths, misunderstandings, and dismissive stereotypes, the final result being that it turns her lack of interest or knowledge about certain genres or filmmakers into a positive good rather than a gap in expertise.

First, let's look at her characterization of Gordon. Sure, I like him enough, but does he really occupy "pride of place, along with zombie auteur George A. Romero, as originators of the cult-horror form"? Stuart arrived on the scene nearly two decades after Night of the Living Dead. The number of directors and movies that arrived in the 20 years between those two flicks, all of which have a much greater claim for being "originators of the cult-horror form" than Gordon. Even among horror fans Gordon's a bit of a one-hit wonder.

As for Argento, perhaps I'm not self-respecting, but I haven't been booted out of the horror blog-o-sphere for thinking Argento's overrated. Maybe the jackbooted film taste police just haven't reached me yet. Or, and I know this sounds crazy, there's simply no goose-stepping central authority of horror fandom. Wait, wait: hear me out. Maybe, just maybe, horror fans are a pretty diverse group of people with varied tastes. Maybe we all apply slightly different critical criteria to the films we enjoy. We engage in dialog with other fans about relative merits. Sometimes we even respect one another's different opinions (not on the Internet, of course, but elsewhere it can happen).

But, then again, I'm not one of those who have spent my entire life in a "sticky-floored repertory house" (shades of the porn theater, that bit), so how I even know about the unbelievably obscure directors is a mystery. In the era of Netflix and the Internet, her characterization of the cult film world is a bizarre fantasy, not unlike the imaginary hordes of socially-stunted troglodyte basement-dwelling bloggers that mainstream literary critics fear are battering down the establishment's draw bridge.

Claiming outsider status is the last refuge of the intellectual bigot. When you can't make a good argument for defending your limited criteria for what makes a good work of art (and we all, by the nature that we don't have infinite capacities for appreciation, have limited criteria), you instead suggest that the issue at hand is that a cabal of elites have foisted what you don't like on you. Genre guys pretend that they've been marginalized by an evil conspiracy of elitist critics. Critics play the same game, simply reversing the positions to become the embattled defenders of true quality. Both sides appeal to the sadly innate American distrust of expertise and love of claiming the status of the righteous victim. You're a victim, fighting for truth and justice. This isn't about the fact that your tastes, knowledge base, and experiences might be ill-suited for the rigorous evaluation of these films. Rather, this is about how you, alone out of all your cynical and mean-spirited film critic ilk, had the mad courage to take a stand. This is what we do with our unexamined prejudices: we dress them up in the shoddy borrowed stage-finery of the "last honest man."

We salute you Ann Hornaday. You're so brave. When the collective weight of the film criticism world crashes down on you for your brave, so very very brave, refusal to toe the line, rest assured that you've got an open invite to guest blog here. Together maybe we can hold our against those barbaric hordes of, shudder to think, cult film fans.

Thursday, June 05, 2008

Books: Semi-rural suburban vampire terror-cells and the hobby-shop ninjas who fight them.

Jonathan Maberry's Dead Man's Song is the sequel to his Stoker-Award winning Ghost Road Blues and it picks up immediately where the previous book left off. And I do mean immediately – the first action starts just a few hours after the last conflict in the first book.