Classical pianist and blogger Jermey Denk ponders the role of classical music in horror flicks, with an emphasis on scenes from Twilight: New Moon and Silence of the Lambs.

As you can imagine, most of the music of Twilight is a spool of new age melancholy-lite with interchangeable aspartame chords and a spectacular disregard for monotony and cliché: the sort of thing you run across 12-year-old girls playing, to express themselves, on upright pianos in junior high chorus rooms after the last tater tots have been shoved down the last pimply gullet of the last smug bully before the last bus creaks out of the parking lot, sending wheezes of diesel sadness into the dusk as yet another chalky day of teaching scrawls to an end . . .

I was just settling in with my movie nachos, just getting used to this aural upholstery–anything that does not kill you, etc. etc.–when (suddenly!) a few notes reminded me that there might be a better world. Bella gets knocked against a wall, her arm’s bleeding and in a flash Dr. Cullen–a vampire who has virtuously pulled back his fake hair and steeled himself to resist his blood-urge–dismisses his weaker, ravenous vampire relatives, and prepares to stitch up her gaping wound. As he stitches, we hear [Schubert's setting of one of Goethe's poems, original post contains an audio file - CRwM].

This was no nacho hallucination! There really WAS a Schubert song lurking in this teen vampire romance … and not just Joe Schubert Song, but a setting of one of the greatest Goethe poems. But why this song? And why Schubert? My mind immediately and shamelessly ran after musicological ramifications: “Schubert is sucking at the neck of the subdominant, to demonstrate vis-a-vis the fangs of his modal mixture the inadequacy of conventional polarities of dominance” . . . Though I dismissed the notion of a hidden musicological agenda I suddenly wondered how many vampires take refuge in the musicology faculties of our nation’s universities.

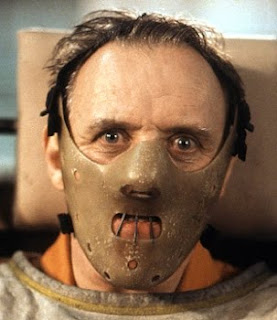

This was one of these moments where Popular Culture decides for a capricious instant that Hundreds Of Years Of The Western Canon are temporarily useful for appropriation; it does classical music a huge favor by Noticing It. Lovers of classical music are supposed to beam and pant like a petted dog, grateful for any and all attention. Wag wag, woof woof, good boy, go play in your cute tuxedo now! Classical music often serves an iconic, representative, dubiously honorable purpose in popular film, and this instance of classical quotation–besides reminding me what a steaming load of crapola I had been listening to previously–reminded me very much of the famous scene in The Silence of the Lambs, where Hannibal Lecter brutally murders and partly eats his two guards to the strains of the Goldberg Variations.

In both these scenes, classical music becomes an emblem of distance and detachment. Cullen is looking directly upon blood without giving in to his hunger; he is practicing Zen-like separation from desire. Lecter has a very different detachment, the detachment required to kill perfectly, ruthlessly, without regret or remorse; his is the detachment, the disconnect, the absence of “normal” emotion which marks sociopathy.In both scenes, the music is ironic. It’s effective in a way that horrific or disturbing, i.e. “appropriate” music would not be. Its meaning lies in its otherness … While Lecter commits one of man’s darkest taboos (cannibalism), behind him rings the decorum and organization of Bach, with its peerless canons and schemes and rules; the Goldbergs whisper to our ears all the connotation and comfort of human Enlightenment, while the Dark Ages scream at our eyes from the screen. Cullen is stitching a raw wound; he fills a bowl full of blood … The camera lingers on both, in the way we imagine Cullen’s eyes unconsciously might; meanwhile the song proceeds in uncanny calm, a calm which feels strange against our sense of a repressed murderousness. The calm is a classical music calm, an alien calm, it evokes the price and pressure of Cullen’s self-repression. I have noticed often that the forces of Hollywood cannot use classical music to express “normal” emotions, but only extremes, only things that must be seen weirdly, in reverse.

In both scenes, blood. Both Lecter and Cullen traffic in blood, and their bloodiest scenes bleed classical music. Yes, we can say, the director is suggesting that classical music is “beauty” against which the horrors of bloodlust are seen more starkly. But if the music is supposed to be the opposite of the bloody scene, isn’t the implication somehow that the beauty of classical music is “bloodless”? Lecter is a soulless monster, and he loves Bach; Cullen is a soulless vampire, who uses Schubert to calm himself while he repairs a wound. Always soulless; always other; always anachronistic; classical music is the preference of monsters. I can see how the age of the music connects to the immortality of the vampire, I can see how the Bach connects to Lecter’s genius, but why must classical music be the language of monsters, of the fringe?