Buried (Under the Fold) Alive, Part I

Like cheese and science, old comments tend to get tossed away. While the occasional post might get a few hits now and then even after it has dropped off the main page, comments are more ephemeral. Recently, ANTSS received two comments that I think deserve a little attention.

First, like many of you, I was approached by the men and women of the NYC-based Charred Oak Films about crowd sourcing their indie horror-comedy Always a Bridesmaid.

Clicky peeky and then come on back.

I don't necessarily want to shill for their flick, but I do think it has the potential to be a winner. Let's face it: Women-centric horror packs them in. The comedy angle makes its tent slightly larger. And another project on their docket, Satan Camp, suggests that these folks can tap into a popular retro vibe.

But, that aside, supporting something like Always a Bridesmaid is a blow against the Empire. Specifically, the Empire of half-assed remakes, follow-the-leader copy cats, cookie cutter, formulaic, Hollywood crappola.

We vote with our dollars. You may have written the most insightful, witty, and devastating critique of Halloween II to ever grace the Interwebs. But I'll tell you what, Skippy; they don't give a crap what you said so long as ponied up like all the other marks.

Imagine this: What if everybody who shelled out ten to twelve Washingtons had, instead, kicked it towards funding an indie horror flick? The estimated budget for Always a Bridesmaid is $16,5000 (nearly one hundredth of the budget for Halloween II). At this point Zombie's flick has made more than $25 million. With that kind of cash, you could fund more than 1,500 films on the scale of Bridesmaid.

Dig hard, babies. This blog gets about 120 visitors a day. For the cost of Manhattan movie ticket, we'd raise more than a grand in a single day.

Like the weather, everybody bitches about the lamification of horror at the hands of talentless bean-counting studio douches. But unlike the weather, we can do something about it.

I'm not silly enough to believe that every indie horror flick is a gem. Nor do I believe that taking big studio scratch is like touching pitch, it blackens the hands. But preserving the diversity of voice in the genre, specifically by acting as patrons and friends to independent and developing, ensures the long term health of the genre. More than any ranting and raving we do as critics, its our actions - specifically our spending - that define us as fans.

Will Bridesmaid be great? Will it suck? I don't know. I hope to find out though. Even if only because it would mean we were all good stewards of our genre.

So, anyway, I kicked 'em a few bucks.

Buried (Under the Fold) Alive, Part II

Speaking of preserving voices . . . The second comment I wanted to draw attention to was attached to the Sprites song I posted a couple days ago. Musician Zane Grant has a nifty musical treat for ya'll. I'll just repeat his intro:

My sister and I did a 'dawn of the dead' song for a cd that retold the stories of different horror movies from the narrative perspectives of people in the movies. I must admit, The Sprites 'Dawn' song is better than ours, but our 28 days later and (drunk) susperia were fun if people want to check them out:

"28 Days Later"

"Suspiria" (drunk take)

Thanks for stopping by Mr. Grant.

Wrap Yourself in Awesome

My favorite merch tie-ins have always been those pieces of swag that appear to have come from the fictional world of the work they promote. It would be all good and well to have a t-shirt with the poster image for Die Hard on it. But it's about a million times cooler to have a shirt that appears to be swag from the Nakatomi Corporation.

The utterly incandescently brilliant t-shirt shop Last Exit to Nowhere mongers just such coolness. Here's some more samples:

Bonnet Rippers?

Now this is non-horror (though perhaps a bit frightening depending, I guess, on your tastes), but it was too odd not to pass along.

Okay, so this isn't horror, but it is too delightfully odd to pass up. There's a survey piece on the new romance subgenre of "bonnet romance" in, of all places, The Wall Street Journal. They're basically Amish/outsider forbidden love tales.

From the article:

Most bonnet books are G-rated romances, often involving an Amish character who falls for an outsider. Publishers attribute the books' popularity to their pastoral settings and forbidden love scenarios à la Romeo and Juliet. Lately, the genre has expanded to include Amish thrillers and murder mysteries. Most of the authors are women.

Here's a sample, from Cindy Woodsmall's bonneter When the Heart Cries:

His warm, gentle lips moved over hers, and she returned the favor, until Hannah thought they might both take flight right then and there. Finally desperate for air, they parted.

Whew. Mother, hide the little ones!

Sure the Englishers dig on it, but what do the Amish think:

While there are no religious strictures against contemporary novels, the church has traditionally viewed fiction as distracting and deceitful, says Donald Kraybill, a senior fellow at the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, a religious studies center at Elizabethtown College.

Some Amish have nevertheless become avid fans. An Amish woman in Lancaster told Ms. Lewis that "all the women in our church district are reading your books under the covers, literally," Ms. Lewis said. Ms. Brunstetter, who lives in Tacoma, Wash., said several Amish families in northern Indiana have played host to book signings in their homes for her "Sisters of Holmes County" series.

Showing posts with label movie. Show all posts

Showing posts with label movie. Show all posts

Friday, September 11, 2009

Tuesday, July 28, 2009

Movies: Over and out.

I have a soft spot for movies that pit their supernatural baddies against members of the armed forces. Properly done, the militarization of the victims of a horror film imparts a sense of genuine conflict. When a bunch of boozed up co-ed nymphomaniac camp counselors find themselves the target of an eight-foot tall semi-undead mass murderer, the action that follows resembles either a ritual sacrifice or the relentless grind of a factory farm meat processing plant. But, replace those teens with a squad of soldiers and you've suddenly got a ball game. The presence of significant levels of firepower, a pre-existing command structure meant to handle decision-making in a crisis, the willingness and capacity to meet violence with violence, training that facilitates teamwork between tactical assets, and an assumed minimal-level of individual competence all suggest that, whatever the flick might throw at them, the soldiers have a real chance at surviving.

I have a soft spot for movies that pit their supernatural baddies against members of the armed forces. Properly done, the militarization of the victims of a horror film imparts a sense of genuine conflict. When a bunch of boozed up co-ed nymphomaniac camp counselors find themselves the target of an eight-foot tall semi-undead mass murderer, the action that follows resembles either a ritual sacrifice or the relentless grind of a factory farm meat processing plant. But, replace those teens with a squad of soldiers and you've suddenly got a ball game. The presence of significant levels of firepower, a pre-existing command structure meant to handle decision-making in a crisis, the willingness and capacity to meet violence with violence, training that facilitates teamwork between tactical assets, and an assumed minimal-level of individual competence all suggest that, whatever the flick might throw at them, the soldiers have a real chance at surviving.Of course, this perception is largely illusory. My wife's mother likes to say, "God never gives you more trouble than you can handle." Horror films work on the opposite premise: The danger you face must always be greater than your capacities. Usually this works through a simple logic of escalation. Evil always rises to the occasion. If you've got a bunch of teens on a summer holiday, then a serial killer will come after them. Replace one of the teens with an ex-cop packing a .44 Magnum and the standard-issue serial killer will upgrade to a tribe of mutant cannibals. Dump the teens, remake the cop into a British soldier, add a half dozen other troopers, and the cannibal tribe will transform into werewolves. And so on and so on until you've got the entire military of a nation on one side and a giant city-stomping monster on the other.

But bigger baddies only get you so far. There's a pragmatic cap on the logic of perpetual escalation. Eventually you end up trafficking in such enormous levels of destruction that it becomes virtually impossible to conceptualize a threat that could withstand the onslaught. One workaround for the escalation problem is to hamstring the troops. You can give them incompetent leadership, place them in a training context that requires they have fake weapons, or cast "weekend warrior" National Guard types as your military personnel. Clever directors can also exploit the martial assumption that superior firepower, expertly applied, is what every situation calls for. Pit the troops against a virus, ghost, psychic phenomena, or other un-shootable thing and you've pretty negated their major advantage. Regardless of how it's done, we know on some essential level that being soldiers won't actually help the film's protags.

Still, the idea that being soldiers should matter is crucial to carrying off a good army versus monster flick. We have to feel that we're watching humanity's last line of defense, the people you'd call to handle this sort of thing, do real battle. If the mechanics of the plot are too naked visible, the actions of the characters take on an insignificance that fails to grab us.

The 2008 mercs versus monsters flick Outpost starts as a serviceable horror/actioner. But the logic behind its villainous otherworldly sci-fi Nazi immortals (not actually "zombies" in any conventional sense of the term, as is often stated) so overwhelms the agency of the soldiers of fortune at the films core that the flick's stripped down structure tips from pleasingly Spartan to smotheringly arbitrary. What starts as tension devolves into a forced march. There's plenty of gunfire, gore, and a rich layer of pulpy technobabble to act as eye glue. But once the audience has grokked that the actions of the protagonists don't have any effect on the plot's direction, the narrow pleasures of the film are undermined by the sneaking suspicion that they're just waiting for the film to run out of bodies.

The film starts with a pleasingly bare bones plot. The representative of a mysterious and unnamed cabal of investors pulls together a seven-man team of mercenaries to retrieve an unidentified item from a long-abandoned World War II Era bunker in an unnamed Eastern European country. This lack of information gives the flick a user-friendly, almost videogame-ish feel that makes up for in narrative efficiency what it lacks in depth. (Some of the deleted scenes available on the DVD include extended sequences that build character backstory and motivation, but director Steve Barker wisely left such distractions on the cutting-room floor).

Shortly after their arrival at the target, the crew is fired upon from dense woods surrounding the bunker. Convinced that they're outgunned, they hunker down. As they explore the bunker, they crew begins to fall prey to a seemingly unstoppable enemy who, despite the mercs best defenses, slips in and out of the bunker, killing with impunity.

In the meantime, their employer reveals that the target of their search is a "unified field generator," a bizarre bit of strangely Buck Rogers-ish tech that sits at the heart of this otherwise straightforward run and gun. Though I recall many Brits bemoaning the historical inaccuracies of American flicks, the backstory regarding the UFG shows that Americans have no monopoly on bad history or science. Attempting to explain the UFG, the employer explains that four forces govern the behavior of matter in the universe. He doesn't say what they are, but so far, so good. He explains that unified field theory explains the link between these forces. Then, he goes of the rails. Basically, in this film, the unified field acts like the "one ring to rule them all" of time and space. With a unifed field – which is less a mathematic explanation of the links between nuclear forces, gravity, and electromagnetism than a new super energy – people could bend the rules that govern physics. We're told that Einstein was working on the unified field until he saw the detonation of the test a-bomb at Los Alamos. Worried about its destructive potential, he stopped working on it. (In fact, Einstein wasn't at the Trinity test, the a-bomb has little to do with unified theory, and the famed physicist never stopped working on unified field theory.)

The Nazis, it turns out, were ahead of the curve on the UFG and used the unified field to experiment on their own troops, turning them into silent, shambling things that can teleport, become solid or immaterial at will, and exist in a sort of timeless neverwhere outside of their bodies (which are piled up, perfectly preserved, in a cell in the bunker).

The rest of the flick follows our ever-dwindling crew as they slowly come to terms with truth about their unbeatable foes and getting soundly thrashed by Nazi ghosts from beyond time and space.

Though somewhat formulaic, the pick gets creativity points for its innovative and quirky monsters. I suspect the repeated use of "zombie" in reviews and commentary about this flick has to do less with intellectual laziness than with the fact that they're virtually impossible to classify using standard horror beast taxonomies. Furthermore, even in its less innovative aspects, the film's shot with a crisp confidence that carries the viewer over the less interesting bits. The acting is well handled, though nobody is given much beyond broad character types to deal with.

Ultimately, the real problem with the flick is that you can practically see the characters' strings being pulled by the director. For all the shouting and firing, characters are powerless to stop what comes their way. This powerlessness drains the fight and kill scenes of their drama and raises questions about the seemingly nonsensical way in which the Nazi unified field ghosts, or NUFGs, behave. (Even the script gives a nod towards this problem by having a character wonder aloud why the seemingly invincible NUFGs are taking so long to kill them all. He receives no explanation.) The end result is a sort of viewer indifference.

Wednesday, July 22, 2009

Movies: But it's got a great personality.

It is pretty easy to dismiss Scott Reynolds's 1997 The Ugly as a cut-rate Kiwi knock off of the far superior Silence of the Lambs. After all, that's pretty much what it is. The flick revolves around a very familiar premise: a woman must conduct personal interviews with a incarcerated serial killer, finding the truth about his past while resisting the caged psycho's efforts to crawl inside her head. Admittedly, The Ugly includes a whole supernatural angle and there's a distinctly un-Silence-ish focus on the life story and thwarted central love of the killer (though, honestly, this seems as if it was heavily "influenced" by Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer); still, it's hard to shake the feeling that you've seen the film's core premise done better.

It is pretty easy to dismiss Scott Reynolds's 1997 The Ugly as a cut-rate Kiwi knock off of the far superior Silence of the Lambs. After all, that's pretty much what it is. The flick revolves around a very familiar premise: a woman must conduct personal interviews with a incarcerated serial killer, finding the truth about his past while resisting the caged psycho's efforts to crawl inside her head. Admittedly, The Ugly includes a whole supernatural angle and there's a distinctly un-Silence-ish focus on the life story and thwarted central love of the killer (though, honestly, this seems as if it was heavily "influenced" by Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer); still, it's hard to shake the feeling that you've seen the film's core premise done better.That said, after the initial disappointment, I found myself digging on The Ugly to a surprising degree. While the plot seems to be, at best, a serviceable jerry-rig of parts from better flicks, the film brings a pleasingly excessive, low-fi, originality to its visual presentation that reminds me of the giddy stylistic excesses of flicks like Evil Dead and Dead Alive. Not that The Ugly has the same splatter aesthetic – compared to the goo and gore of those other two films, The Ugly is downright demure. Rather, like Evil Dead and Dead Alive, The Ugly loses its stylistic inhibitions as it goes along, getting aggressively odder and more boldly quirky even as it settles in a predictable narrative mold. The film gives off a sort of film tech geek charm, a product of its formal playfulness, that I thought was genuinely amusing.

For example, during one of the film's many flashbacks to episodes within our killer's bloody career, we see Simon (the film's homicidal protagonist) off a dude outside a rock club. The scene's only soundtrack is the power pop that, one assumes, is pouring out of the club. Simon catches a glimpse of a witness: a young girl inside what appears to be an abandoned furniture factory next to the club. Simon bursts into the club after her and, once inside, the music stops and the film is silent. Watching this scene, I assumed that the change in the soundtrack was strictly diegetic. The sound cut off because the characters where now isolated from the source. However, as Simon and his witness play a frantic game of hide and seek in the factory, the sound cuts in and out, alternating between blasting cheese rock and silence. Ok, I thought, so it isn't diegetic; instead, the filmmakers are having a little fun with sound design. However, at the end of the scene, Simon catches the witness and notices that she's got a non-functional hearing aid. She's deaf. The sound was, in fact, diegetic from the start and it was switching from the Simon's "point-of-hearing" (if that's a term) to the witness's throughout.

The film's playful style isn't always so clearly in the service of some descriptive or thematic function. Throughout the film, for example, blood is depicted as being inky black in color (except for one odd scene at the end of the flick where blood runs a standard red). Why? I have no idea. One could also make a drinking game out of every time an empty shopping cart appears on screen. I might be missing some profound significance empty shopping carts have in New Zealand culture, but I doubt it. They're there because they're there. Drink.

There's also the curious acting style that's too straight-faced to be overtly campy, but too broad to be considered realistic. This is most notably true of Roy Ward's Dr. Marlow, who seems like a bizarre impersonation of a B-movie asylum warden. As the movie goes on, even Marlow's outfits get more and more like something out of Mark Robson's 1946 crazies-and-costumes melodrama Bedlam. And his final scene is so inexplicable as to be laugh inducing, and intentionally so I think.

Still, unlike Jackson or Raimi's films, The Ugly never just takes off the breaks and goes nuts. Both Evil Dead and Dead Alive fulfill their narrative designs by the three-quarter mark and then become a sort of plotless action/comedy splatter showcases. In contrast, The Ugly has a narrative arc it is wedded to and that keeps it from spinning off the rails. Which is unfortunate as the plot is the film's weakest element and this forced march along a very well tread saps the energy of the flick, chills the mood, and smoothers the wild energy that might have elevated it to cult fave status.

Wednesday, July 11, 2007

Movies: Oh, you meant the other Tarantino.

Just like his more famous namesake, the Tarantino behind the 2005 haunted office spook-flick Headhunter is a writer and director. But unlike Quentin, Paul Tarantino's films – including a second 2005 project called I Shot Myself (presumably not autobiographical in nature, but that might be justified) – have not become the toast of Cannes, have never been considered milestones of contemporary cinema, and are not likely to spur intense devotion and cult status on the auteur.

Just like his more famous namesake, the Tarantino behind the 2005 haunted office spook-flick Headhunter is a writer and director. But unlike Quentin, Paul Tarantino's films – including a second 2005 project called I Shot Myself (presumably not autobiographical in nature, but that might be justified) – have not become the toast of Cannes, have never been considered milestones of contemporary cinema, and are not likely to spur intense devotion and cult status on the auteur.Headhunter is low-budget horror fare that gets off to a rocky start, takes a promising turn, and then collapses so thoroughly that, by the end of it, even the cast and crew seem to have lost any sense that it should be horrific, settling instead for sub-Zucker grade silly.

The plot involves an insurance salesman who, after taking a tip from a wealthy client, ends up seeking the assistance of a corporate headhunter. Luckily, this headhunter – a hottie-boombalottie blonde with a bit of a temper – keeps odd office hours and is available to see our hero in the middle of the night. I should point out that our hero does not find the headhunter's creepy, nocturnal manner – or the homeless dude that hangs outside of her office warning people not to enter her lair – sufficiently off-putting to cause him to seek a headhunter who, say, has lights installed in their office.

The headhunter hooks him up with a new gig that involves him working the night shift, reviewing actuary charts or some such thing.

It is during this bit, when our hapless insurer starts his new gig, that the movie is at its best. The contemporary office is a criminally underused setting for modern horror. Temporary and deliberately soulless, most offices have all the charm and warmth of Eastern German secret police interrogation centers. There is something genuinely monstrous in there cookie-cutter monotony – as if the spaces were intentionally designed to crush the humanity out the workers who toil away there. Dim the lights of your everyday white collar cube farm and you've got yourself a primo little setting for your horror flick.

As an aside, the wonderful Kings of Infinite Space - a gem of a novel by James Hynes – think Office Space meets The Island of Doctor Moreau, published the same year Headhunter was released – uses the creepy emptiness of office spaces to great effect. This is your bit of added value – instead of watching this flick, do yourself the favor and go read Kings of Infinite Space.

Where were we? Oh, yes. So, when Mr. Indemnity starts his new job, we get a genuinely creep set of scenes that really use the dim, emotionally deadening office set to perfect effect. It is truly creepy.

Unfortunately, it all goes downhill from there. The scares fail to scare, the one sex scene fails to titillate, and the spooky tone developed so wonderfully evaporates as we stumble our way through an increasingly goofy plot.

Headhunter falls in that unforgiving ground between slight entertainment and so-bad-it's-good. After some promise, it fails to keep one involved and never gets so silly or outrageous that it enters into the realm of transcendent badness. It is, sadly, bad in a purely uninterestingly bad way. Dusting of the old Purported Diet of David Bowie in His Thin White Duke Phase Film Rating System, I'm giving this flick a rating of "milk." It is a disaster or some crime against humanity – in fact, it would be worth more consideration if it were.

Monday, May 14, 2007

Movies: 28 Weaks Later

There's something telling about the fact that 28 Weeks Later is the second flick this season to feature a scene in which zombie hordes are dispatched via the rotors of a flying helicopter. The "whirly bird as undead Cuisinart" meme first popped up in the Planet Terror portion of Grindhouse as a joke. In 28 Weeks Later, a very similar scene is played totally straight-faced. I don't think this is, necessarily, an indication of how little creativity there is in the modern mainstream horror flick. Instead, it points to only real weakness in what is otherwise an excellent film: 28 Weeks Later suffers from being just one more solid zombie flick in a era of countless zombie flicks.

There's something telling about the fact that 28 Weeks Later is the second flick this season to feature a scene in which zombie hordes are dispatched via the rotors of a flying helicopter. The "whirly bird as undead Cuisinart" meme first popped up in the Planet Terror portion of Grindhouse as a joke. In 28 Weeks Later, a very similar scene is played totally straight-faced. I don't think this is, necessarily, an indication of how little creativity there is in the modern mainstream horror flick. Instead, it points to only real weakness in what is otherwise an excellent film: 28 Weeks Later suffers from being just one more solid zombie flick in a era of countless zombie flicks.In many ways, 28 Days Later, the superior predecessor to Weeks, benefited from being in exactly the opposite position. Days would have been a notable flick under any circumstances. It is a truly brilliant addition to the zombie cannon. It is well-written, beautifully shot, filled with characters you actually cared about, and is genuinely frightening. It even contains the occasional art-house flourish (the impressionistic field of flowers digitally painted into the flick, for example) to let you know that the folks behind the cameras didn't feel they were slumming. But what ultimately put 28 Days into great category was that it was a fresh look at a sub-genre that had been dormant and free of any major hits for several years. It didn't have to compete with dozens of other zombie films, most bad, some great, and all taking up the same cognitive space.

Now, a couple years after Days and seemingly hundreds of zombie flicks later, Weeks, with a solid script, good acting, and excellent camera works, seems like just another generic zombie movie. The chronological distance between Days and its sources made the film seem like an homage. Some of the films Weeks seems to reference are less than a year old. Is that an homage? Or just lazy filmmaking?

In a way, this is a shame. Weeks is a solid film. The flick follows a handful of different characters: a man haunted by the fact that he abandoned his wife during a zombie attack, two children returning to post-zombie London, and several members of the US-led UN force attempting to re-colonize the UK. We have a larger cast of characters, but the scope of the story demands it and I don't think the film lost anything for being able to spend less time developing the roles of our protagonists. There are several exciting scenes, though they are often more thrilling and action-packed than frightening. The film is less visually striking, but not in any incompetent way. The sequel eschews (sorry, I've been trying to think of a way to work eschew into more reviews) the original's indie-influenced aesthetic for something closer to the rapidly edited, big screen bang of a major action blowout. There's more gore and chewy bits, though the MTV-style editing means it goes by in a flash.

If fact, as far as the actual making of the film itself, I've only one major beef. Much is made in the flick of assumed parallels between the re-colonizing forces in the flick and the current situation in Iraq. Mainly, the theory is, that US soldiers show up claiming to help, but turn out to be willing to oppress and even destroy the locals in order to maintain order and suppress the spread of the rage virus (which, in a bit of retro-continuity, we're told never jumped species – though, as I recall, we got it from monkeys). The allusions aren't subtle – US forces, for example, operate out of the "Green Zone" – so even if your primary source of news is Jon Stewart, you won't miss the topical references. There are two problems with this. First, the metaphor doesn't hold water. In terms of the filmic world of Weeks, the threat from rage is real and the consequences of an uncontrolled outbreak could be globally devastating. The fictionalized US didn't invent a cause to go occupy London nor are they under-estimating and understating the threat. The idea that military forces shouldn't react swiftly and definitively to control the spread of the disease is questionable at best. Worse it leads to a situation where the filmmakers seem to have characters reacting not to the situation described in the flick, but to the situation the film is alluding to. This means our heroes do things that would be heroic if they were in a real desert war somewhere, but are just incredibly dumb given the story of the film. I give the filmmakers credit for not portraying the US army as a bunch of evil yahoos – they are conflicted folks with unique personalities, each deciding whether they will or will not go along with the occupational authorities. But, ultimately, the situations just aren't morally comparable and the whole thing seems distracting.

Second problem is that we've already seen this particular analogy done better. In fact, we've seen it twice recently: in Land of the Dead and 28 Days Later. Which brings us back to the zombie saturation issue. It is time to give zombies a freakin' rest. 28 Weeks Later marks an interesting point in the latest zombie trend: as of the release of this film, it is now possible to make a really good zombie film and still not escape the general fatigue of the sub-genre as a whole. Even a great zombie flick will now just be another zombie flick. Because of this, using the Defunct Hindu Political Parties Movie Rating System, I'm giving 28 Weeks Later a middling Bharatiya Jana Sangh. If this was still 2003, 28 Weeks Later would have rocked the living daylights out of me. Now it is a case of too little, too late.

Labels:

28 Days Later,

28 Weeks Later,

movie,

zero new ideas later

Tuesday, April 03, 2007

Movies: I walk the line. With a zombie.

Way back when, in the Golden Age of the Hollywood studio system, even their cheapies seemed classier. At least, you'd think so checking out Val Lewton produced double-header I Walked with a Zombie and The Body Snatcher. Part of the 5 disc/10 movie Lewton retrospective released by Turner Entertainment, this two-for-one disc is a prime specimen of the top notch, classy, gothic film Lewton produced during his brilliant, but brief, four-year run as head of RKO's horror unit: a run that produced at least one certifiable horror classic a year and exploited the talents of several then-minor but soon to be famous directors.

Way back when, in the Golden Age of the Hollywood studio system, even their cheapies seemed classier. At least, you'd think so checking out Val Lewton produced double-header I Walked with a Zombie and The Body Snatcher. Part of the 5 disc/10 movie Lewton retrospective released by Turner Entertainment, this two-for-one disc is a prime specimen of the top notch, classy, gothic film Lewton produced during his brilliant, but brief, four-year run as head of RKO's horror unit: a run that produced at least one certifiable horror classic a year and exploited the talents of several then-minor but soon to be famous directors.A little backstory on Lewton before we hop into the two flicks. Born Vladimir Leventon, the future director came to America with his family when he was five. Though it doesn't seem to have done him much good, he was the nephew of the scandal-ridden silent screen vamp Alla Nazimova. Lewton spent most of his early career as a freelance writer. He cranked out copy for newspapers (he was booted from one paper for fabricating a story about a mass kosher chicken die-off during a New York heat wave), weekly magazines, the pulps, and even wrote a bit of pornographic erotica. Anything to pay the bills. The name Val Lewton was originally a nom de plume. Vlad used it on the cover of a few of his novels before picking it up semi-permanently for the movie biz.

In 1933, Lewton got a job work for David O. Selznick. He acted mainly as a story editor, but the job morphed into something more like a behind-the-scenes jack-of-all-trades. During this time, he famously contributed several scenes to Gone with the Wind - most notably the long crane shot of what seems to be endless rows of Confederate wounded, suffering and expiring under a waving Confederate flag. For nearly a decade he ran around the RKO lots, doing random chores and picking up the movie biz through osmosis. In 1942, he was appointed the head of RKO's horror unit. He was to crank out crowd pleasing theater fillers, in a hurry and on the cheap.

Funny thing happened, though. Lewton turned a steady profit and filled the theater seats with fare that was definitely down market – he once said, "You shouldn't get mad at New York reviewers. It is actually very hard for a reviewer to give something called I Walked with a Zombie a good review" – but, in hindsight, it is clear he also made some very good films. Lewton's horror flicks are literate, well shot, thoughtful, and steeped in a classic gothic sensibility. His movies were so much better than they needed to be that, even now, they can take the viewer by surprise. You settle down, expect some good old-school horror cheese, and, instead, you're pulled into the work of a man film critic James Agee claimed was one the three most creative figures in Hollywood.

I Walked with a Zombie is often considered Lewton's finest outing. Based on a series of "scientific" articles about the practice of voodoo in Haiti, Lewton decided the original story was weak on narrative drive and wed the zombie and voodoo trappings to a rough re-working of the plot of Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre. In Lewton's hybrid, a young nurse is hired by a wealthy sugar plantation owner to care for his wife, in a coma like state since suffering a rare tropical disease. There she is pulled in the gothic family politics of the plantation and the hidden world of voodoo thriving outside the walls of the estate. Despite its European-gothic-by-way-of-voodoo-magic exploitation angle, the semi-anthropological thrust of the original articles was not lost on Lewton and the finely realized details of the film make it one of the few Hollywood horror films in any era to treat voodoo and the Caribbean culture that created with a modicum of sincere respect. Many of the most effective moments of the film deal not only with the horrors of voodoo magic, but with the enduring legacy of slavery and colonialism.

The film also benefits from the pairing of Lewton and one of his most accomplished regular directors: Jacques Tourneur, director of the horror classic The Cat People and the noir landmark Out of the Past. Tourneur's use of lighting and set and his smooth, polished professionalism, all conspire to give I Walked with a Zombie a classic look and feel that completely transcends its poverty row origins. You feel like your watching some strange, surreal A-picture.

In the second feature, The Body Snatcher, Lewton again benefits from an excellent director. This time the director seat holds up the talented ass of Robert Wise, who would later go on to direct The Day the Earth Stood Still, Run Silent, Run Deep, West Side Story, The Sound of Music, The Sand Pebbles, and, one of my favorite horror flicks, The Haunting. (He also did the first Star Trek film, which isn't my cup of tea, but regular reader Screamin' Dave might get a kick out of the mention.)

The Body Snatcher, loosely based on a Robert Louis Stevenson short story, follows the misadventures of two 19th century doctors who find themselves blackmailed by the murderous grave robber who supplies their medical school with cadavers. Wise's film is somewhat hampered by a too-chatty script, but it does boast something Tourneur's film lacks: a wonderful performance by Boris Karloff as the Gray, the sadistic body snatcher. It also features Bela Lugosi in a minor, but effective role.

Neither of these films is truly frightening by modern horror standards. Instead, it is probably better to think of them as gothic dramas, maybe even horror melodramas. Still both films are classics of the genre and well worth your time. Using the Lifetime Achievements of William Withering Movie Rating System, official movie rating system of the European Union, I give I Walked with a Zombie a superb "invention of digitalis" rating and The Body Snatcher a somewhat lesser, but still fine "first English-language botany text to use Linnaean taxonomy." A solid two-film package.

Friday, March 23, 2007

Movie: There was something awfully familiar about the way that male nurse grabbed that half-naked chick.

First off, Prison of the Psychotic Damned (also know as Prison of the Psychotic Dead) is a great title. The Psychotic Damned would be enough for most flicks. Prison of the Psychotic or Prison of the Damned, both equally fine, if not particularly grabbing titles. But there's something about the pile of all the terms together, jamming all these loaded terms together, but cutting it just before it lapses into parody (Bloody Cursed Torture Asylum of the Homicidally Psychotic Hungry Damned for Beyond the Grave) that promises solid horror entertainment.

First off, Prison of the Psychotic Damned (also know as Prison of the Psychotic Dead) is a great title. The Psychotic Damned would be enough for most flicks. Prison of the Psychotic or Prison of the Damned, both equally fine, if not particularly grabbing titles. But there's something about the pile of all the terms together, jamming all these loaded terms together, but cutting it just before it lapses into parody (Bloody Cursed Torture Asylum of the Homicidally Psychotic Hungry Damned for Beyond the Grave) that promises solid horror entertainment.And, for the most part, PPD manages to deliver on that promise. Partially because of the occasional flashes of real talent that went into this low budget shocker; but partially because the makers of PPD had a secret weapon: one of the most photogenic horror sets in recent history. PPD tells the story of a team of paranormal investigators who, in order to investigate reports of supernatural activity, spend a single hellish night in Buffalo's long-abandoned Central Terminal railway station. Most of the film appears to have been shot on location and, as far as sets go, Central Terminal ranks up there with The Shining's Overlook Hotel and Session 9's Danvers Hospital. Once an awe-inspiring art deco shrine to the romance and power of train travel, Central Terminal fell into disuse and decay. The faded grandeur of the station is powerfully evocative of past times, of people and dreams gone – in short, the place just looks haunted. Furthermore, the epic scope of the structure dwarfs the actors, as if the haunted station, without the help of special effects scares, was threatening to swallow them. Every shot the camera captures within Central Terminal can't help but capture the station's gothic, spooky atmosphere.

Though most of this film's punch comes from the great set, its story isn't without its charms. The filmmakers wisely decided to stick with a reliable, but still flexible formula. Sure, we've seen paranormal investigators get what's coming to them since the Wise's superlative The Haunting (actually, I've seen a few great silent short films from the 1920s that use the same plot, but let's stay canonical for this discussion), but the basic formula allows enough room for interpretation that a clever filmmaker can use its conventions as a frame without being caught in a rut. In fact, the film's weakest points are when it rambles away from the plot. For example, a short intro focusing on a particularly busty character flipping out in her flophouse apartment seems overlong. (This particular scene is only redeemed by the gratuitous nudity it involves and by the appearance of regular commenter and all around nice guy Screamin' Cattleworks – ladies, calm down, Screamin' Cattleworks is not the one who gets gratuitously nude.)

For the most part, however, the film works well enough that the budgetary restraints and the strictly serviceable acting don't become bothersome. Well enough, in fact, that many of the scares are genuine. The director even knows when to pass on the obvious scare in favor of building up the tension and teasing the audience just slightly. In the hands of an incompetent director, tricks like that fall on their face. But here, the succeed more often then they fail.

PPD is not a great horror flick – except that one scene with Screamin' Cattleworks that will change forever the way you think about male nurses wrestling with half-naked women. It is the work of devoted and talented people with, perhaps, more genre knowledge and moxie than actual movie-making chops. Still, there's enough good stuff here to keep the interest of the viewer and the movie never feels like a slight throw away. I suspect the viewer feels a little of the earnest intention of the filmmakers: they want to make something fun, and a little scary, that didn't suck. That's as noble and honest a goal as you're likely to find among contemporary filmmakers. Using my recently revised Butterflies of India Film Rating System, I'm giving Prison of the Psychotic Damned a fine, if not socks rockin', Common Cerulean. Yeah, it ain't no monarch or nothing, but it is still a butterfly and that's not half bad.

Thursday, March 08, 2007

Movies: Don't quit your day job.

When Shakespeare wrote "It is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing," I'm almost certain he was talking about the truly mediocre Audition by the consistently "oh-so-shocking" Takashi Miike, the tirelessly prolific standard-bearer of Asian extreme cinema.

When Shakespeare wrote "It is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing," I'm almost certain he was talking about the truly mediocre Audition by the consistently "oh-so-shocking" Takashi Miike, the tirelessly prolific standard-bearer of Asian extreme cinema.For those who haven't seen this flick, I'm about to drop major spoilers all over this review; though, to be honest, the film's lethargic pacing and complete lack of interest in causality mean that the very concept of a spoiler is somewhat inapplicable.

Here we go. The plot of Audition involves a widower who, at the prodding of his son, who like dinosaurs (I mention this because it is the most salient bit of characterization Miike gives us regarding the son), decides to get remarried. Problem is the widower doesn't really have a particular woman in mind. He just wants to get married. This sort of thing counts as a psychological motivation in the world of Audition.

The widower explains his problem to a showbiz amigo of his and the buddy offers to hold auditions for fake flick. The widower can pick his new wife out of the clutch of wannabe actress that show up. This sort of thing strains credulity when it serves as the basis for a comedy, but Audition treats this moronic plan with an almost epic gravitas that would itself be funny if the flick appeared to be in on the joke. What, is Internet dating to straight forward? One almost wonders why nobody suggests he should dress a woman in order to truly meet his future wife before he proposed.

Anyway, the auditions go well and the widower finds the mysterious, by which I mean painfully un-emotive, woman of his dreams. The two lovers go on a series of dates so stilted that they'd be painful to watch if the pace of the movie wasn't so soporific it numbed viewers beyond the capacity to care. Supposedly the widower gets obsessed by love, though this is depicted mainly through long shots of him starring at the telephone with an expression that resembles the look of a man wondering if the feeling is his stomach is nausea or gas.

Throughout, the audience has been privy to the fact that the mystery girl seems to spend her free hours sitting in a unfurnished home, sitting next to the phone, and watching a dude she keeps in a sack roll around. Apparently, we're supposed to think this behavior is weirder than the behavior of a dude who invents a fake movie so he can select his future wife from a stack of wactresses' résumés.

Like one does when one meets a mysterious girl whose references don't check out (or maybe they do – we're told early in the film that none of he references connect with real joints – but later in the flick, we watch the widower use them to track her down), the widower conspicuously avoids introducing the girl to his friend or his son. Instead, he decides that their third date will be a beach getaway where he'll pop the question. He takes his would-be bride to a cute little hideaway and they make sweet, stilted love.

Then she disappears in the middle of the night. She's suddenly gone without a trace.

She no longer returns widower's calls and his obsession/appearance of gastrointestinal discomfort gets worse. Eventually he launches on a search for her, using all the leads in the résumé we were told were nonexistent. The widower meets a pervy crippled dance instructor and finds out the owner of the bar that employed mystery girl got brutally slaughtered.

Finally, everything comes to a gory conclusion when the mystery woman shows up at the dude's house to torture him to death for the whole audition ruse thing. Seriously. She thinks that lopping the widower's feet off and sticking needles in him is commensurate with the crime of lying to her.

One could argue that her being a serial killer and not bringing it up is equally dishonest, but Miike seems to actually be on her side. During the interminably un-shocking "climax" of the flick, we find out that the widower also once slept with a woman he works with, but did not pursue the relationship further. This tidbit is apparently supposed to further explain why this dopey son of a bitch gets butchered and treated like a human pincushion.

It seems that repeated incidents of childhood sexual abuse have turned our mystery girl into a highly efficient and knowledgeable amateur torture enthusiast. We are, it seems, meant to equate the widower's stupidity and regrettable, but hardly uncommon, insensitivity with this early exploitation. According to the NYTime's Elvis Mitchell, the flick is about "the objectification of women in Japanese society and the mirror-image horror of retribution it could create." But there's the problem: how is the fact that the widower is a bit of a clod in anyway the "mirror-image" of actions of the girl in the picture? Her gory assault on the widower is so asymmetrical as to seem to come from another movie. The only way it works is with the comic book logic that used to fuel stuff like the old EC titles, where robbing cash is sufficient justification for being eating by cannibals and the like. Only EC delivered this heavy handed "ethical stance" with a knowing smirk that was the honest admission that they understood you'd come for the scares and not the moral edification. Miike wants you to take his juvenile, ham fisted morality play for real.

A literal description of Miike's flick is the best summary: after nearly two hours of fruitless searching, we get a nonsensical bloody mess. Using the unforgiving Stops on the Kryvyi Rih Metrotram Line Movie Rating System, I'm giving this humorless, pretentious lemon a Zarichna. And I doubt it deserves all that.

Friday, February 09, 2007

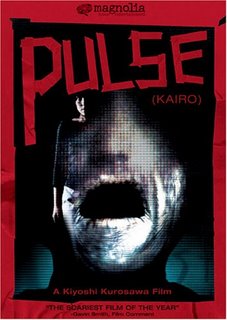

Movies: They should call the sequel "Re-Pulse."

First, an apology.

First, an apology.I've been a lousy blogger and my posting pace, once a heroic post-a-day, has dwindled to a downright stingy twice a week. I can only claim work pressures and ask you for a little more patience. I hope, soon, to get back to my old once a day schedule. Until then, I'll post when I can.

Now . . . some horror stuff.

While working his way through a generic J-horror knock-off of The Ring – complete with haunted communications mediums and an overly elaborate rules for dying and not dying – something weird happened to director Kiyoshi Kurosawa: he stumbled upon an odd, artsy flick about the existential loneliness of the human condition. Even weirder, instead of punching the clock and turning in the next Ring-let, Kurosawa (no relation) made the film less shot. And, for Pulse (2001), it has made all the difference.

Pulse starts with all the necessary elements of a generic J-horror flick. A group of young, banal middle-class urban types accidentally comes across a bit of media – in this case a Web site instead of a video cassette – that serves as a gateway between this world and the next. This site gets linked to suicides happening all over Japan. The spirits of these suicides ending up on this site, mostly just sitting around, seemingly bored for all eternity. Oh, sometimes one of these dead souls calls the cell phone of a living person, though how or why is unclear and somewhat irrelevant as the dead have nothing to say but, "Help me" over and over.

As if a plague of suicides wasn't enough, some people are suffering death-by-becoming-wall-stains. Seriously. They get really sad and then fade into the nearest solid object, leaving behind a brown and black metaphysical skid mark on the wall or floor.

The explanation, for what it is worth, is that the spirit world has run out of real estate. The dead are eyeing the living world with plans for Chavez Ravine-style land grab. Only, where to put the living? You can't kill them. That'd just make more ghosts, which would just contribute to the afterlife overpopulation problem. Instead, the ghosts "trap the living in their own loneliness." Which is to say: "Make wall stains out of them." Anybody who doesn't want to become a wall stain will kill themselves instead. These folks get their souls safely diverted into the media-sphere, which can hold souls. Problem solved!

Follow all that?

Along the way, people will see several standard model Japanese-made pale, long haired ghosts. There's this whole thing about making doorways to the spirit world with red duct tape (again, I'm serious) And, eventually, the suicides and stainages reach apocalyptic proportions, and we watch a few confused and lost survivors try to make their way through a depopulated and haunted Japan.

Like almost every J-horror flick I've seen, Pulse relies on complexity over logic. They pile up arbitrary and senselessly evolving rules around their spooks and monsters, taking an almost Dadaist joy in rules that exist simply for the sake of rules. And, normally, that pisses me off. The unnecessarily complex, but ultimately not all that important, mythologies of J-horror are a disappointing drain on my viewing pleasure. Take The Ring for instance. The franchise was not improved by the addition of more backstory, especially as it all came at the price of making a complete mess of the wonderfully simple rules that drove the first flick.

Pulse, however, did not piss me off. I think this is because, about half way through, the film simply quits caring about being a horror movie and instead approaches something like a lyric meditation on loneliness. It is horrible, but in that way that the death of somebody after a lingering illness is horrible. It isn't shocking so much as sadly sobering. There are a few scary scenes, but mostly the mood is melancholy and introspective. As the film goes on, the various characters drift into long, empty silences. The streets empty out. People look upon the bodies of the dead with, what? Long? Sadness? Incomprehension?

In one stand out scene, a plane, presumably once piloted by somebody who is now a stain on the cockpit instrumentation, crashes in front of one of the film's main characters. Instead of playing it as an action scene, our lead silently watches as the plane, trailing a long tail of thick smoke, makes a slow and lazy arc. It crashes off-screen. Our protagonist doesn't run to investigate. She doesn't bother to go search for survivors. What, one imagines her thinking, would be the point?

Like They Came Back, the strange and sorrowful French zombie flick that used the trappings of a horror movie as an excuse to explore human sadness, Pulse is a thoughtful little art flick in the ill-fitting clothing of a horror flick. It is less successful than They Came Back in combining the two genres and I can imagine that many horror fans found this flick a complete bore. Personally, I was frustrated with the flick until I realized that this flick had morphed into something other than a straight horror picture and I should adjust my expectations accordingly.

Once you get over the bait and switch, Pulse is an okay film. It looks good. The story follows a sort allegorical logic that can carry you through the more tangled narrative patches. Ultimately, however, the flick suffers from being not quite a horror flick but not quite an art film, the two competing goals clash more than they blend. In situations like this, I find the Homeplanes of the Dungeons & Dragons Role Playing Game Film Rating System works best. Pulse gets a fair "Concordant Domains of the Outlands" rating. Sure it's concordant, but it is still of the outlands, you know?

Friday, February 02, 2007

Movies: Trying too hard to prove we're smarter than the dudes who cooked up "Alien vs. Predator."

The idea of a sci-fi monster mash betwixt the acid-blooded aliens of the Aliens franchise and the dreadlocked great invisible hunters of the Predator franchise is one of those seemingly obvious ideas that, in fact, contains a hidden flaw that the finished flick makes obvious.

The idea of a sci-fi monster mash betwixt the acid-blooded aliens of the Aliens franchise and the dreadlocked great invisible hunters of the Predator franchise is one of those seemingly obvious ideas that, in fact, contains a hidden flaw that the finished flick makes obvious.Two flaws, actually.

First, the franchises are, if you think about it, in two different leagues. Aliens, if you count strictly the canonical flicks, has run through four films. Each flick was helmed by a major directorial talent (Ridley Scott, James Cameron, David Fincher, and the French guy whose name completely escapes me, you know, that guy), each flick featured at least one big name actor, and all of them were major productions. The Predator franchise, however, has spawned only two flicks. The first built around the rock-stupid action character persona of Arnold, the second around the tired Lethal Weapon persona of Glover. Neither had an A-list director at the wheel – the firtst being the product of the workman-like John McTiernan, the second being the work of Stephan Hopkins fresh from Elm Street 5: The Dream Child, his incomprehensible addition to Kruger franchise. In short, as fun as the Predator franchise is, it simply doesn't play in the same league as Aliens. It is somewhat like teaming up Anthony Hopkins' Hannibal Lecter with Chucky – sure they're both serial killers from horror movies, but there's a qualitative difference that would make such a team-up more of a joke than a genuine fright fest. In this flick, the aliens felt diminished and wasted because they'd been shoehorned into a lesser product.

Second, the Predator was the star of his franchise. Though Arnie was perhaps one of the most bankable names at the time the first flick was shot, the reason why we still remember Predator was that it took a forgettable, typical Arnold actioner and flipped it. The soldier boys of Predator purposefully seemed like they wandered in from the jungles of any of a hundred 80's shoot 'em ups. It is the presence of the alien game hunter that brings the film to life. The aliens of the Aliens series, however, have always been more like the zombies in Romero's Dead franchise. They are the stars of the flicks, but the real drama comes from watching humans deal with them. They are not, themselves, particularly interesting, from a cinematic point of view. They look cool, but they tend to just hiss and bump into one another and crawl on the walls aimlessly until you give them some astronauts or space marines to chew on. Then they become this force which puts humans under pressure and gives us a classic "trapped and surrounded, will they band together?" plot. The aliens make for good film because of what they make humans do.

AVP, as the cool kids call it, places the aliens and predators front and center, losing what makes the aliens cool and concentrating way more attention to the Predator than it can take. The film is a silly, pointless romp that never gives viewers enough of anything to really make it worth its hour and a half running time.

That said, I'd like to turn my attention to perhaps the best thing one can say about this flick, and that is that the film inspired some truly delightful reviews on Netflix.

The best of which comes from a dude who calls him- or herself "The Astrodart." The Astrodart (like The Cheat, I think you need to include the The whenever you mention The Astrodart) gave the flick one star and then proceeded to provide a series of questions meant, I think, to poke holes in the plot of movie that centers around giant space bugs fighting a race of aliens who, like interstellar gun-nut rednecks, have based their entire culture on recreational hunting. Unfortunately, The Astrodart's efforts are as funny as the movies flaws. The Astrodart begins the "deconstruction" thusly:

Rather than give a straight review of the steaming pile that is "AVP," I'd like to critique the movie by asking several relatively spoilerless questions. Why would there be a whaling station in Antarctica in 1904?

Well, the filmmaker probably thought they could feature an Antarctic whaling station from 1904 in their film because there was a really a whaling station on Antarctica in 1904. Before the creation of factory ships, whalers need Antarctic whaling stations to help process their catches. The first processing station went up in 1904, on Grytviken, South Georgia. Now, to be fair, this isn't something I knew off the top of my head. I had to Google it – but, presumably, anybody who can post a review on Netflix can Google "Antarctica whaling stations" and not begin their clever assault with a utter dud. Astrodart, The, then launches into a series of probing questions:

Why does no one's breath steam in the sub zero temperature of the south pole? Why don't the predators in this film use stealth and intelligence like the other movies? If the predators' weapons are acid proof, why not their armor? Why do the chest burster aliens pop out of people's bodies in a few minutes rather than incubate for a day or two? How do said chest bursters fully mature after another ten minutes or so?

The first one seems fair; though, to me, a question like "how could aliens have evolved in such a manner as to be perfectly adapted to incubate inside what appears to be an infinite number of host species?" seems like a considerably stickier wicket. Or, perhaps, more interesting, "how is it that aliens never have to eat?" They turn many of their victims into egg hosts; but even when they don't, they usually leave their corpses behind or so vastly outnumber potential food species that they'd burn through the population and starve to death. As for why armor would melt, but not weaponry, perhaps they're made of two different materials like, oh, I don't, modern weapons and body armor. Finally, do we have a timetable for alien gestation and development? Is it any less absurd that a creature with an exoskeleton would mature in a day, sans shed shells, than it is that such an animal would be lethal in minutes? Basically, my point is that the whole concept is fairly absurd, so this outrage at perceived plot holes strikes me as bizarre. How you can set your personal absurd-o-meter high enough to accept the aliens and predator species, but still sweat this crap is beyond me.

Still, for all The Astrodart's quirky questions, he or she didn't take the lazy way out. There are several reviews which basically use this construction:

I could systematically dissect this movie and give a detailed breakdown of exactly how awful this movie is, but honestly, it’s just not worth the effort.

This is just a tease! Either unleash critical Hell or don't, but this "I could kill, but you aren't worth my time" thing is lame. How valuable can your damn time be that you're leaving a review of Aliens vs. Predator on Netflix?

I knew this kid when I was young – Richard Fellman – who swore he knew karate, but could never show us anything because he was only supposed to use the deadly art in self-defense. Nobody believed him. He was, in fact, a big lame-o. I have a proposal. From now on, when somebody posts a review where they suggest they could demolish a movie with their keen critical insights, but do not because it would not be worthy of them, we call that "posting a Fellman."

Did people do this before the Internet era, when anybody could instantly preserve their weird hissy-fit for all eternity? I reckon they did.

Lord Waddleneck: Verily, Lady Macbeth claims she knows what 'tis like to nurse a child, but 'tis made clear their marriage is a barren one. Odd's blood! For sooth, such lapses logickal are apt to throw me into a most intemperate rage! And a child born of a section de Caesar is not born of woman? The groundlings may enjoy such contrivances inane . . .

Sir Autumnbottom: By my troth, t'would serve if I did raze this foul drama with mine bodkin sharp wits – but gross combat with one so unfit t'would be unseemly.

Labels:

Lord Waddleneck,

monster mash,

movie,

sci-fi,

Sir Autumnbottom

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)