First, an apology.

First, an apology.I've been a lousy blogger and my posting pace, once a heroic post-a-day, has dwindled to a downright stingy twice a week. I can only claim work pressures and ask you for a little more patience. I hope, soon, to get back to my old once a day schedule. Until then, I'll post when I can.

Now . . . some horror stuff.

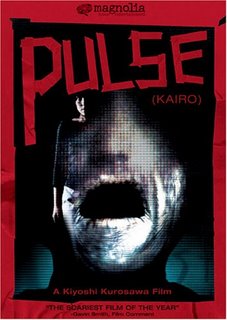

While working his way through a generic J-horror knock-off of The Ring – complete with haunted communications mediums and an overly elaborate rules for dying and not dying – something weird happened to director Kiyoshi Kurosawa: he stumbled upon an odd, artsy flick about the existential loneliness of the human condition. Even weirder, instead of punching the clock and turning in the next Ring-let, Kurosawa (no relation) made the film less shot. And, for Pulse (2001), it has made all the difference.

Pulse starts with all the necessary elements of a generic J-horror flick. A group of young, banal middle-class urban types accidentally comes across a bit of media – in this case a Web site instead of a video cassette – that serves as a gateway between this world and the next. This site gets linked to suicides happening all over Japan. The spirits of these suicides ending up on this site, mostly just sitting around, seemingly bored for all eternity. Oh, sometimes one of these dead souls calls the cell phone of a living person, though how or why is unclear and somewhat irrelevant as the dead have nothing to say but, "Help me" over and over.

As if a plague of suicides wasn't enough, some people are suffering death-by-becoming-wall-stains. Seriously. They get really sad and then fade into the nearest solid object, leaving behind a brown and black metaphysical skid mark on the wall or floor.

The explanation, for what it is worth, is that the spirit world has run out of real estate. The dead are eyeing the living world with plans for Chavez Ravine-style land grab. Only, where to put the living? You can't kill them. That'd just make more ghosts, which would just contribute to the afterlife overpopulation problem. Instead, the ghosts "trap the living in their own loneliness." Which is to say: "Make wall stains out of them." Anybody who doesn't want to become a wall stain will kill themselves instead. These folks get their souls safely diverted into the media-sphere, which can hold souls. Problem solved!

Follow all that?

Along the way, people will see several standard model Japanese-made pale, long haired ghosts. There's this whole thing about making doorways to the spirit world with red duct tape (again, I'm serious) And, eventually, the suicides and stainages reach apocalyptic proportions, and we watch a few confused and lost survivors try to make their way through a depopulated and haunted Japan.

Like almost every J-horror flick I've seen, Pulse relies on complexity over logic. They pile up arbitrary and senselessly evolving rules around their spooks and monsters, taking an almost Dadaist joy in rules that exist simply for the sake of rules. And, normally, that pisses me off. The unnecessarily complex, but ultimately not all that important, mythologies of J-horror are a disappointing drain on my viewing pleasure. Take The Ring for instance. The franchise was not improved by the addition of more backstory, especially as it all came at the price of making a complete mess of the wonderfully simple rules that drove the first flick.

Pulse, however, did not piss me off. I think this is because, about half way through, the film simply quits caring about being a horror movie and instead approaches something like a lyric meditation on loneliness. It is horrible, but in that way that the death of somebody after a lingering illness is horrible. It isn't shocking so much as sadly sobering. There are a few scary scenes, but mostly the mood is melancholy and introspective. As the film goes on, the various characters drift into long, empty silences. The streets empty out. People look upon the bodies of the dead with, what? Long? Sadness? Incomprehension?

In one stand out scene, a plane, presumably once piloted by somebody who is now a stain on the cockpit instrumentation, crashes in front of one of the film's main characters. Instead of playing it as an action scene, our lead silently watches as the plane, trailing a long tail of thick smoke, makes a slow and lazy arc. It crashes off-screen. Our protagonist doesn't run to investigate. She doesn't bother to go search for survivors. What, one imagines her thinking, would be the point?

Like They Came Back, the strange and sorrowful French zombie flick that used the trappings of a horror movie as an excuse to explore human sadness, Pulse is a thoughtful little art flick in the ill-fitting clothing of a horror flick. It is less successful than They Came Back in combining the two genres and I can imagine that many horror fans found this flick a complete bore. Personally, I was frustrated with the flick until I realized that this flick had morphed into something other than a straight horror picture and I should adjust my expectations accordingly.

Once you get over the bait and switch, Pulse is an okay film. It looks good. The story follows a sort allegorical logic that can carry you through the more tangled narrative patches. Ultimately, however, the flick suffers from being not quite a horror flick but not quite an art film, the two competing goals clash more than they blend. In situations like this, I find the Homeplanes of the Dungeons & Dragons Role Playing Game Film Rating System works best. Pulse gets a fair "Concordant Domains of the Outlands" rating. Sure it's concordant, but it is still of the outlands, you know?

3 comments:

Ignorant question: I'm guessing J-horror flicks don't have teenage sex romps or anything ? No kinky afterlife ghost sex with the living or anything like that ? I mean, the stereotype of J sexual fetishes makes me wonder why not express those in film as well..

Oh, those flicks are out there. But they rarely get the Hollywood remake treatment.

During the 1980s, when American studios were discovering the financial joys of low-budget slasher-style pics, the Japanese studio system was in economically dire times. A combination of tight budgets and an emphasis on safe fare drove a lot of Japanese filmmakers to innovate outside of the studio system.

Partly as a provocation, partly just 'cause they could, many of these filmmakers cranked out extreme horror flicks - featuring buckets of gore and loads of bizarre sex.

Despite extreme Asian horror cinema's popularity with American horror hounds and would-be rebel tastemakers, it kind of represented a filmic dead end in Japan. Most of the dude's who worked in the idiom never made it into the mainstream.

There was, however, a sort of unintended side effect of the growth of the extreme horror movement – it spurred a direct to video market. One of the guys to exploit the smaller budgets of direct-to-video was a Norio Tsuruta, whose Scary True Stories trilogy was the template for what people think of when they now think of J-horror. He even introduced the popular "ghost girl with the long black hair" motif into J-horror.

The reason why we have such a clear image of what constitutes "Japanese horror" has to do with the huge influence of this one series on what became the up and coming generation of Japanese horror directors.

I haven't seen a lot of J-horror. My introduction to it was with "Tetsuo Iron Man", many years ago. Though I haven't seen anything like it since, it comes to mind first when I think of Japanese horror.

I'm not sure what's up with the repeating theme of the ghost girl with long black hair. I guess it's more popular with the kids these days? I did enjoy the American remake of "The Ring", and not to sound like a broken record, but once again it was a film where I enjoyed the buildup and cinematography much more than the eventual reveal.

Post a Comment