Vaughan of Mind Hacks discusses an unusual case human's seeing meaning - specifically, in this case, a human face - in random data. He tells it better than I do:

This is quite possibly the oddest example of an illusory face I have ever discovered.

Seeing meaningful information in meaningless data is a psychological effect known as pareidoia or apophenia and this is an example that was published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1996:

The case of the haunted scrotum

A 45-year-old man was referred for investigation of an undescended right testis by computed tomography (CT). An ultrasound scan showed a normal testis and epididymis on the left side. The right testis was not visualized in the scrotal sac or in the right inguinal region. On CT scanning of the abdomen and pelvis, the right testis was not identified but the left side of the scrotum seemed to be occupied by a screaming ghostlike apparition (Figure 1). By chance, the distribution of normal anatomical structures within the left side of the scrotum had combined to produce this image. What of the undescended right testis? None was found. If you were a right testis, would you want to share the scrotum with that?

J R Harding

Consultant Radiologist, Royal Gwent Hospital

Pic below:

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

Saturday, January 09, 2010

Meta: Awards season.

Seems like everybody is giving everybody awards these days. And, as living proof that surplus drives down value, even I've received one! That's right, loyal Screamers and Screamettes, horror blogger and nifty person Sarah, of the blog Scare Sarah, has awarded your humble horror host with the Kreativ Blogger award.

Seems like everybody is giving everybody awards these days. And, as living proof that surplus drives down value, even I've received one! That's right, loyal Screamers and Screamettes, horror blogger and nifty person Sarah, of the blog Scare Sarah, has awarded your humble horror host with the Kreativ Blogger award.Regular readers know that I generally don't get into the meme-award thing, but it seems like everybody's having a grand old time with these things lately and it's been some time since I've shouted out to some of the blogs I dig, so away we go.

First, I've gathered that I'm supposed to tell you seven interesting things about myself. I promise you that I can definitely tell you seven things about me. Whether they're interesting or not, well . . .

Thing the One:

I have this fantasy in which I go back to sixth-grade, but fully possessed of everything I know and have learned up to this point in my life. I know that I should use this foreknowledge to fight injustice, stop 9/11, and head off the AIDS crisis - but what I honestly imagine doing is learning guitar and preemptively stealing every song that I ever dug and condensing several decades of musical awesomeness into a single, unbelievable rock career that would make me the undisputed God of Rock. Aside from the sketchy ethics of stealing (even though, technically, these songs didn't yet exist when I stole them), the real flaw in this plan is that my musical tastes are pretty goofy, so the idea that anybody would somehow be more excited by my preemptive versions of, say, Daisy Chainsaw's "Dog with Sharper Teeth" or Left Lane Cruiser's "Big Mama" than they were when these songs first appeared and then sank into obscurity is wrong-headed at best.

Thing the Two:

I once started writing a novel that was about a quartet of custom-porno filmmakers who get hired by a cryptofascist multimillionaire to make large-scale hardcore flick set in the Holocaust. I got five or six chapters into it when my hard drive died and the novel was lost forever, which, considering, was probably not such a terrible thing to have had happen. It's working title was Camp Romance.

Thing the Three:

I have three tattoos. The first of which was inflicted upon me in a Richmond hotel room by a woman who actually went by the professional moniker Teddy Bear. Though Teddy Bear was quite lovely and talented, what she was not was fluent in Chinese. Consequently the Chinese figure I have permanently stained on my skin apparently means nothing. It's nonsense in a language I can't read. Despite this, I'm still quite fond of it.

Thing the Four:

When I was 17, I was briefly wanted by the FBI. As silly as this sounds, it was all a big misunderstanding and I was never arrested or charged with anything.

Thing the Five:

I once calculated the estimated number of books that I could read assuming I live to the average age of an American male. This was a massive mistake. For years I would avoid reading books that looked fun because I would think, "Is this really so great that it should be one of your remaining [fill in countdown number]?" Eventually, I got over this obsession. I'm glad I never did it for films; I probably would have never started a horror blog.

Thing the Six:

I wish the term "bedswerver" - a now neglected slang term for an unfaithful person - came back into common usage. It is so wonderfully descriptive.

Thing the Seven:

My wife and I once debated getting a cat as a pet. We brainstormed some names and we thought that they were all so good that we couldn't eliminate any of them. So we hit on this plan that we would give the cat a rotating name. We'd place a chalkboard in the kitchen and write "This week the cat's name is:" on it. We'd work through the names we already had and add new ones as they struck our fancy. We figured the cat wouldn't mind as it was unlikely to give a crap what we called it. (The same plan, we theorized, would not work for a dog.) We purchased a chalkboard and mounted it on the kitchen wall. But we never got a cat.

Okay, now on to who gets the award. Since this is the Kreativ Blogger award, I think it should go to a blog that goes beyond the standard "thumb's up/thumb's down" reviews, net trawled "coverage" of pop culture, and you're predictable "I Googled it, then wrote it" analysis. I'd also like to use it draw attention to a great blog I haven't really plugged before.

I give this to the Mark and ShadowBanker, the boys of Ecocomics. The vast majority of comics writing on the Web is little more than fanboy mash notes and poison pen letters. Admittedly, the quality of the material discussed might be a little more highbrow and the writing more nuanced or clever than the chatter on the floor of the NYCC - but really it comes down to the same thing: People telling you what they liked and hated, ad nauseum. Emphasis on nauseum.

Ecocomics instead takes familiar material and, by applying economics concepts to it in an accessible and entertaining way, actually opens up the material to fresh understandings. Instead of arguing about superhero decadence or lamenting some random creator's political biases, Ecocomics reminds me of the geeky joys of playfully overthinking the characters and concepts I love. Remember those silly/great arguments about who could beat who in a fight? Remember obsessing about continuity contradictions? Ecocomics manages to evoke the pleasures of that sort of active fan engagement without the normal schmaltz of dweeb nostalgia. It reinvests the comics with possibilities and a sense of pleasure.

There's a lot of great writers out there ready to tell you what they enjoyed. Ecocomics is one of the few comic blogs out there that invites you to enjoy comics with them.

Friday, January 08, 2010

Books: Whose woods are these I think I know.

When I was a college radio DJ - back in the prehistoric days when music came imprinted onto the surfaces of solid objects and "streaming" was an adjective used mostly in conjunction with urination - we had this goofy in joke that hinged on unnecessary intensification. It worked like this: Describe X by taking Y, which possesses trait T to a high degree, and claim that X is Y if Y had T to a high degree.

When I was a college radio DJ - back in the prehistoric days when music came imprinted onto the surfaces of solid objects and "streaming" was an adjective used mostly in conjunction with urination - we had this goofy in joke that hinged on unnecessary intensification. It worked like this: Describe X by taking Y, which possesses trait T to a high degree, and claim that X is Y if Y had T to a high degree.We were radio DJ's, not stand-up comedians.

We'd say stuff like, "That band's like Jesus Lizard, if Jesus Lizard was a noisy toxic spill of raging rockness" or "Sarah is like Amy, if Amy was a cold and unforgiving iceberg." (For the record, "cold and unforgiving" was the key to Amy's stupidly insane hotness; like so many sexual Shakletons looking to discover magnetic south, Amy's attractive pull to the dumber of the species was directly proportionate to how likely the effort to conquer was to end in your demise - but I digress.) It was an unnecessarily convoluted way to say how intensely Y possessed T. To put it in a horror blog context, we'd say, "August Underground is like the Guinea Pig series if the Guinea Pig series was a gory, f'ed up mess" or "That post is like a horror blog 'top' list posts if 'top' list posts were lazy, lame fan-service circle jerks." It was Bergsonian joke: The ha-has came from how inefficient a way to express yourself it was. Plus, there was humorous assumption of ignorance at work because you pretended not to really get X. It doesn't work in a blog so good.

Anywho, I bring this up because, at first glance, Richard Laymon's The Woods Are Dark seems to have been earnestly built on the premise of writing a Off Season if Off Season was violent and savage. The comparison between Laymon's book and Ketchum's book is unavoidable. Both feature vacationers in a fight against atavistic cannibal tribes. Both books foreground the idea of turning savage in order to survive. Curiously, both books even suffered similar fates at the hands of their editors: Off Season and The Woods Are Dark were famously butchered by their original publishers, only to be restored in complete texts decades later.

Despite these similarities, Laymon's book plays at a very different game. Though neither book is particularly realistic, Laymon's work becomes a grim and fantastic allegory about the relative sense of civilization and the "us versus them" mentality that may be one of humanity's most essential psychological tools. It ultimately shares more with Jackson's The Lottery and The Wicker Man than Ketchum's gore soaked thriller.

That Laymon's books is a curious world-building exercise is easy to overlook. World-building is often synonymous with purple prose excess and baggy exposition: Think of all the torturously bad poetry and unnecessary genealogical asides scattered about the works of Tolkien. Laymon's compact prose rockets the story along. His style is an odd sort of trick: He uses a hard-boiled minimalism to construct a bug's-eye view of a surprisingly large fantasy vision. Nowhere is this taut style better on display than the opening chapters of the book. Laymon wastes no time introducing our protags and throwing them into harm's way. The books opens with a splatter of surreality: Two friends, Neala and Sherri, on a driving holiday get a hand thrown at their car by a legless mutant on the roadside. Seriously. That's how the story starts. It's all done in a paragraph or two.

Neala and Sherri stop at a greasy spoon in Barlow, the next town they reach, and debate their responsibilities with regards to reporting hand-throwing mutant half-people. The debate quick tips in the realm of academic when the other patrons of the restaurant rise up and kidnap our heroines. They are trucked out remote location in the woods where they are joined by the three members plus guest of the Dill family, vacationers who were snatched from a Barlow motel.

The six captives are bound to a stand of much-abused trees and left there. It doesn't take long for the prisoners to realize their fate: They've been left as a sacrificial offering to the Krulls, a savage tribe of cannibals that have kept a grim and uneasy truce with the people of Barlow. The people of Barlow regularly drop off a handful of outsiders - the men and the old get eaten, the young women are kept for recreation and breeding purposes - and the Krulls don't prey on the folks of Barlow. What neither the prisoners nor their would-be slayers know is that, on this particular night, the nasty, but effective truce between Barlow and the Krulls is going to collapse. Instead of the regular sacrifice, and impulsive and dissatisfied young man from Barlow decides to buck the system and free the hostages/dinners. This act leads to a horrific two-day battle between the hostages and the Krulls.

The plot is familiar. If you've seen any horror film in the past three decades that contains characters who could be described as "hillbillies," then you know the drill. And, admittedly, there's a lot of factory standard stuff in here: We get all the highlights of the subgenre, from the body parts as fashion wardrobes to the ineffectual post-feminist era spineless intellectual who must suddenly become as vicious as his enemies to defeat them. Laymon occasionally pushes the elements further than most - Lander Dill, the transformed milquetoast, actually becomes a psycho looney who is far more dangerous to everybody around him than the Krulls are - but, for the most part, he hits these marks with an energy and enthusiasm that is effective if not original. (I hate to side with the forces of Big Publishing - those clueless mainstream editors who horror fandom is absolutely certain just don't get it - but much of the restoration work done on this novel centers on the Lander Dill plotline. In this case, Big Publishing was correct. Lander is the novelist weakest link. His transformation from wussy to dubiously sane killing machine seems insincere and so broad as to be comical. It is Laymon's only major misstep and whatever editor trimmed that subplot down is to be commended, not condemned.)

Where Laymon's truly unique contribution to the subgenre is comes in is his expansion of the worldview of the Krulls. Originally presented as wild beasts, Laymon turns a surreally nasty anthropologist's eye on his fictional tribe of regressives and fleshes them out to a degree similar stories never bother. Over the course of the novel, we comes to learn how the Krulls see themselves: A pure strain outlaw community that lives only by the primal laws of nature. We get their origin mythology, which is a bizarre cross between Genesis and the rugged individualist frontiersman tropes of our own civic religion. And, ultimately, come to understand that they view themselves as humans beset on all sides by enemies as concrete as the savage man creature that shares their wood (a odd, possibly supernatural man-bearish thing that they believe to be their Adamic ur-father turned demonic persecutor) and as abstract as the modernity they are fully aware of, but reject. This is not to say that the reader sympathizes with them. The Krulls' woods aren't even a nice place to visit. But Laymon shows that not only are they fully human, but even capable of sacrifices that, according to the own grim mores, are sincerely poignant. There are moments, brief transcendent shards of pure unadorned sympathy with raw humanity, that pierce though Laymon's depiction of the Krulls that remind me of John Smith's diaries of the Jamestown settlement or Jean De Lery's History of a Voyage to the Land of Brazil. That sense of an alien world that reveals itself to be, after all, recognizably human - but still fraught with the potential for danger and unspeakable horror - infuses Laymon's book at its best moments. It's the Krulls you miss when the bog is done. (And, personally, I'd love more about the citizens of Barlow. Laymon seems to forget them, even to the point of not considering what happens when the survivors tell their tale to the authorities. There's a massive search of the woods, so they do tell the police what happened. But wouldn't that mean that the citizens of Barlow are in deep doodoo? We never find out. Frustrating!)

I thank ANTSS regular Shon for giving me the opportunity to enjoy this book. It was a genuine pleasure.

Wednesday, January 06, 2010

Music: "I shed the blood of the Saxon men!"

So the always classy Christopher Lee is releasing a "symphonic metal" concept album.

For real. I shit you not.

It's rock opera about the life of Charlemagne.

Here are some excerpts.

For real. I shit you not.

It's rock opera about the life of Charlemagne.

Here are some excerpts.

Tuesday, January 05, 2010

Mad science: Zombie animals.

Scientific American, a magazine whose title increasingly sounds like a deliberate and almost provocative anarchronism (like the CP in NAACP), has a nifty article and slide show on behavoir-changing parasites: parasites that not only infect a host, but hijack existing behavoirs and twist them to better serve the spread of the parasite. Here's two examples from the article:

In the case of the spooked spider (Plesiometa argyra), a parasitic wasp (Hymenoepimecis argyraphaga) lays her eggs on the spider's abdomen. Just before the larva emerges, the host spins a strange, new type of web—one that looks nothing like its usual wide nets. This silk platform, however, is perfectly suited to supporting a cocoon for the vulnerable young wasp larvae, which have been feasting on the spider's innards as they grow.

The snail-manipulating flatworm (Leucochloridium paradoxum) grows and multiplies inside the snail. Once ready to move on to its next host, the worms push up into the snail's tentacles, making them swell and squirm, mimicking the action of bugs that birds like to eat. As the snail crawls, blindly, into the sunlight, a passing bird is likely to swoop down to snatch a tasty tentacle or two. The worm-infested meal will then infect the bird, which passes it onto other snails via dubious droppings.

Monday, January 04, 2010

Mad science: Lost in Pandora.

Over at the Frontal Cortex, there's an interesting, if kind of disturbing, assessment of Avatar as an example of the fully realized potential of the medium of film.

From the mind of Jonah Lehrer:

The modernist critic Clement Greenberg argued that art should be evaluated on its adherence to the "specificity of the medium". Painting, for instance, is defined by its abstract flatness, which meant that artists should no longer try to pretend that what they convey is real. While centuries of "realist" artists tried to escape the flatness with elaborate technical tricks, Greenberg argued that the flatness wasn't an obstacle or hurdle: it was merely an essential element of painting. This led Greenberg to become an advocate for people like Jackson Pollock, who celebrated the 2-D un-reality of their art form.

The point, though, is that every art is defined by its medium. The reason I've referenced Greenberg in the context of Avatar - and please pardon the pretentiousness of the above paragraph - is that I think Cameron has deftly realized the potential of his medium, which is film.

Lehrer then goes on to discuss a neuroscience experiement that suggests movie audiences react to film, from a neuro-biological perspective, in surprisingly standardized ways. According to the work of Uri Hasson and Rafael Malach, the brains of film-goers "'tick together' in synchronized spatiotemporal patterns when exposed to the same visual environment." Their research indicates that that, across individuals, the visual cortex, fusiform gyrus (the area responsible for face, color, word, number, and category recognition), and areas related to touch activated. It was also notable what areas didn't activate: "Our results show a clear segregation between regions engaged during self-related introspective processes and cortical regions involved in sensorimotor processing. Furthermore, self-related regions were inhibited during sensorimotor processing. Thus, the common idiom 'losing yourself in the act' receives here a clear neurophysiological underpinnings." In short, we divert processing power from critical, self-evaluative functions to sensory processing functions.

I should note here that the flick used in the study was the spaghetti western classic The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

That's all Kool and the Gang, but why would this mean the flick with the giant Native American Smurf cats is the ultimate expression of film? Lehrer explains:

At its core, movies are about dissolution: we forget about ourselves and become one with the giant projected characters on the screen. In other words, they become our temporary avatars, so that we're inseparable from their story. (This is one of the reasons why the Avatar plot is so effective: it's really a metaphor for the act of movie-watching.) And for a mind that's so relentlessly self-aware, I'd argue that 100 minutes of self-forgetting (as indicated by a quieting of the prefrontal cortex) is a pretty nice cognitive vacation. And Avatar, through a variety of technical mechanisms - from the astonishing special effects to the straightforward story to the use of 3-D imagery - manages to induce those "synchronized spatiotemporal patterns" to an unprecedented degree. That is what the movies are all about, and that is what Avatar delivers.

I'm all aboard Lehrer's neuro-just-so explanation of Avatar's unique power. I haven't seen it, but the fact that nearly everybody praises the film in terms of its uniquely immersive qualities seems to jibe with the lick Lehrer's putting down. What's my problem then? Well, my problems are legion and it would take another blog to answer that question - but focusing on this particular issue, I have a problem with Lehrer's claim that "at its core, movies are about dissolution." And not just because the sentence suffers from pronoun troubles.

The problem with Hasson and Malach's study, as well as with Lehrer's overreaching application of their results, is that it is dishonest about what constitutes our understanding of the word "movie." Both the original study and Lehrer selected specific kinds of films: narrative films in recognizable genres, heavy on plot. This isn't meant to be dismissive of these flicks, even Lehrer claims it is case with Avatar: "I was lost in Pandora, transfixed by a perfectly predictable melodrama." But there are plenty of movies out there that break that mold. Even if we don't evoke the complete abstract works of most extreme film experimentalists, we can wonder about the lab results that Palindromes - a flick that regularly swaps in and out actors to play a single lead character - would have had on the viewer activation patterns. What about the ol' reliable French New Wave, with its constant, intentional breaking of film's magic immersive spell? Is Masculine, Feminine: In 15 Acts really a less artistically achieved film than Avatar because it refuses to let you get lost in it?

On a related note, the ability to "get lost in a film" would seem to me to considerably more than a function of the medium's formal elements. I recall, from my youth, a Washington Post film review - name long forgotten - reviewing the rap-centric Spinal Tapish satire CB4. The review used the phrase "like taking the SATs in Martian." The barrier to entry was not, one assumes, Tamra Davis's experimental filmmaking techniques. Davis's work is fine example of clear storytelling. Rather, it is a purely social thing: Without access to the semantic level of the film, which required a slightly more than passing acquiantance with rap music, the formal level failed to produce phenom - presumably because it failed to produce the activation pattern - that both the researchers and Lehrer suggest is inherint to powerful films. One could argue, as I will for the sake of argument, that the the "dissolution" of film is an individual phenomenon. That Avatar is a brilliant film for Lehrer and, presumably, there was some "perfect viewer" that got CB4's brilliance. (His name was Justin Goslin. He thought that movie was the funniest shit he'd ever seen, man.) But then shouldn't we, by extension, assume that films like Derek Jarman's Blue and Warhol's Empire have perfect viewers too? In which case we lose the argument that the formal elements of the films in question are responsible for the effect reported. Empire lacks story elements and editing. Blue is a steady field of the titular color with dialogue over it. Admittedly, these are extreme cases, but I feel we're justified in interrogating Lehrer in this way because he's not just making an aesthetic judgment regarding Avatar, but claiming that there's a element of scientific fact at the core of his judgment. To like Avatar is one thing. To make a claim for the neuro-reality of the film experience and then gloss it with value judgment is another.

I get where Lehrer's going with this, but the "film as cognitive vacation" thing rubs me the wrong way. Not because films that serve that function are inferior or shouldn't be enjoyed, but rather because it suggests that films should never aspire to be anything other than, literally, mass delivered sedatives for our critical faculties. Like the tired notion that comics are inherently "childish" by viture of the features of their medium, Lehrer's definition of film, and his expectation of the pleasures film can provide us, assumes a certain level of mindlessness. Indeed, it makes it the medium's highest virtue. Why straightjacket film that way?

From the mind of Jonah Lehrer:

The modernist critic Clement Greenberg argued that art should be evaluated on its adherence to the "specificity of the medium". Painting, for instance, is defined by its abstract flatness, which meant that artists should no longer try to pretend that what they convey is real. While centuries of "realist" artists tried to escape the flatness with elaborate technical tricks, Greenberg argued that the flatness wasn't an obstacle or hurdle: it was merely an essential element of painting. This led Greenberg to become an advocate for people like Jackson Pollock, who celebrated the 2-D un-reality of their art form.

The point, though, is that every art is defined by its medium. The reason I've referenced Greenberg in the context of Avatar - and please pardon the pretentiousness of the above paragraph - is that I think Cameron has deftly realized the potential of his medium, which is film.

Lehrer then goes on to discuss a neuroscience experiement that suggests movie audiences react to film, from a neuro-biological perspective, in surprisingly standardized ways. According to the work of Uri Hasson and Rafael Malach, the brains of film-goers "'tick together' in synchronized spatiotemporal patterns when exposed to the same visual environment." Their research indicates that that, across individuals, the visual cortex, fusiform gyrus (the area responsible for face, color, word, number, and category recognition), and areas related to touch activated. It was also notable what areas didn't activate: "Our results show a clear segregation between regions engaged during self-related introspective processes and cortical regions involved in sensorimotor processing. Furthermore, self-related regions were inhibited during sensorimotor processing. Thus, the common idiom 'losing yourself in the act' receives here a clear neurophysiological underpinnings." In short, we divert processing power from critical, self-evaluative functions to sensory processing functions.

I should note here that the flick used in the study was the spaghetti western classic The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

That's all Kool and the Gang, but why would this mean the flick with the giant Native American Smurf cats is the ultimate expression of film? Lehrer explains:

At its core, movies are about dissolution: we forget about ourselves and become one with the giant projected characters on the screen. In other words, they become our temporary avatars, so that we're inseparable from their story. (This is one of the reasons why the Avatar plot is so effective: it's really a metaphor for the act of movie-watching.) And for a mind that's so relentlessly self-aware, I'd argue that 100 minutes of self-forgetting (as indicated by a quieting of the prefrontal cortex) is a pretty nice cognitive vacation. And Avatar, through a variety of technical mechanisms - from the astonishing special effects to the straightforward story to the use of 3-D imagery - manages to induce those "synchronized spatiotemporal patterns" to an unprecedented degree. That is what the movies are all about, and that is what Avatar delivers.

I'm all aboard Lehrer's neuro-just-so explanation of Avatar's unique power. I haven't seen it, but the fact that nearly everybody praises the film in terms of its uniquely immersive qualities seems to jibe with the lick Lehrer's putting down. What's my problem then? Well, my problems are legion and it would take another blog to answer that question - but focusing on this particular issue, I have a problem with Lehrer's claim that "at its core, movies are about dissolution." And not just because the sentence suffers from pronoun troubles.

The problem with Hasson and Malach's study, as well as with Lehrer's overreaching application of their results, is that it is dishonest about what constitutes our understanding of the word "movie." Both the original study and Lehrer selected specific kinds of films: narrative films in recognizable genres, heavy on plot. This isn't meant to be dismissive of these flicks, even Lehrer claims it is case with Avatar: "I was lost in Pandora, transfixed by a perfectly predictable melodrama." But there are plenty of movies out there that break that mold. Even if we don't evoke the complete abstract works of most extreme film experimentalists, we can wonder about the lab results that Palindromes - a flick that regularly swaps in and out actors to play a single lead character - would have had on the viewer activation patterns. What about the ol' reliable French New Wave, with its constant, intentional breaking of film's magic immersive spell? Is Masculine, Feminine: In 15 Acts really a less artistically achieved film than Avatar because it refuses to let you get lost in it?

On a related note, the ability to "get lost in a film" would seem to me to considerably more than a function of the medium's formal elements. I recall, from my youth, a Washington Post film review - name long forgotten - reviewing the rap-centric Spinal Tapish satire CB4. The review used the phrase "like taking the SATs in Martian." The barrier to entry was not, one assumes, Tamra Davis's experimental filmmaking techniques. Davis's work is fine example of clear storytelling. Rather, it is a purely social thing: Without access to the semantic level of the film, which required a slightly more than passing acquiantance with rap music, the formal level failed to produce phenom - presumably because it failed to produce the activation pattern - that both the researchers and Lehrer suggest is inherint to powerful films. One could argue, as I will for the sake of argument, that the the "dissolution" of film is an individual phenomenon. That Avatar is a brilliant film for Lehrer and, presumably, there was some "perfect viewer" that got CB4's brilliance. (His name was Justin Goslin. He thought that movie was the funniest shit he'd ever seen, man.) But then shouldn't we, by extension, assume that films like Derek Jarman's Blue and Warhol's Empire have perfect viewers too? In which case we lose the argument that the formal elements of the films in question are responsible for the effect reported. Empire lacks story elements and editing. Blue is a steady field of the titular color with dialogue over it. Admittedly, these are extreme cases, but I feel we're justified in interrogating Lehrer in this way because he's not just making an aesthetic judgment regarding Avatar, but claiming that there's a element of scientific fact at the core of his judgment. To like Avatar is one thing. To make a claim for the neuro-reality of the film experience and then gloss it with value judgment is another.

I get where Lehrer's going with this, but the "film as cognitive vacation" thing rubs me the wrong way. Not because films that serve that function are inferior or shouldn't be enjoyed, but rather because it suggests that films should never aspire to be anything other than, literally, mass delivered sedatives for our critical faculties. Like the tired notion that comics are inherently "childish" by viture of the features of their medium, Lehrer's definition of film, and his expectation of the pleasures film can provide us, assumes a certain level of mindlessness. Indeed, it makes it the medium's highest virtue. Why straightjacket film that way?

Saturday, January 02, 2010

Movies: Like the actual experience of war, I just wanted it to be over.

I picked up George Hickenlooper's Grey Knight - shilled overseas with the infinitely cooler title of The Killing Box - with low expectations. I was expecting a hammy Southern revanchist horror flick about crazed hillbillies, with a schmeer of post-Glory Civil War class and Apocalypse Now guerra matto.

I picked up George Hickenlooper's Grey Knight - shilled overseas with the infinitely cooler title of The Killing Box - with low expectations. I was expecting a hammy Southern revanchist horror flick about crazed hillbillies, with a schmeer of post-Glory Civil War class and Apocalypse Now guerra matto.What's actually in the Grey Knight package is an odd fusion of Ken Burn's Civil War docu-epic and Victor Halperin's sadly under discussed Revolt of the Zombies. And, honestly, as far as inspirational shotgun weddings go, that's not half bad. Plus, on paper, the flicks got a pant's load of talent of talent to thrust that premise with gusto. Director George Hickenlooper was fresh off his brilliant documentary Hearts of Darkness. Monte Hellman, elder statesman of independent American cinema, was holding the editor's razor. In front of the camera, there's a cast full of competent actors: Corbin Bernsen, Adrian Pasdar, Billy Bob Thornton, Martin Sheen, David Arquette - admittedly not the greatest show ever assembled under one roof, but certainly enough talent to get this strictly B-grade fright flick off the ground.

So, why do the results feel so lackluster?

Grey Knight suffers because it can't commit to its own weird premise. Either because Hickenlooper didn't think a monster pic was worth the effort or because he simply grew interested in narrative threads and themes peripheral to the main plot, the finished product feels schizo. In fact, the divided intention is so strong that one can almost tease out the other flick, the one I suspect Hickenlooper really wanted to make.

Let's talk about the movie that actually ended up in the can. Set at the height of the War of Northern Aggression, the stories centers around two principles: A union tracker named Thalman and a former Reb officer turned-POW named Strayn. This duo gets put in charge of the effort to find and neutralize a rogue group of Confederate and Union troops who are attacking Northern and Southern forces in Tennessee. Aside from showing the minimal effort at target discrimination that we use as the thin moral line between "just war" and "inhuman slaughter," this rogue group further distinguishes itself by crucifying the men it takes prisoner. The prisoners are hung upside down, nailed to a crude X of wood.

As it turns out, the renegade group is actually possessed by evil African spirits called the Makers. Once trapped in a well by the warriors of a tribal village, these spirits were freed by slave traders. These traders than brought the spirits to North America where (from what I could understand of the backstory) enslaved descendants of the original warrior tribe trapped them in a underwater cave in Tennessee.

We get all this backstory from Rebecca, a mute psychic ex-slave who comes long on the expedition to 1) give the viewer exposition on a need to know basis and 2) provide Strayn with a highly dubious shot at racial and historical redemption by becoming his love interest. Unable to speak for herself, she exists mainly so that the white characters in the film can position themselves with regards to the race issue. This embarrassingly clichéd character is all the more painful to watch because she's played by the talented and fiercely beautiful Cynda Williams, whose participation in this film was a brief pause between the sad end of her promising early career (Mo' Better Blues and One False Move) and the start of her transition to cheesy softcore (Wet and Condition Red). That filmmakers couldn't find anything better for Williams to do than to play a mute liberated slave who falls for a Confederate officer says something deeply sad about Hollywood.

But back to the film.

The Makers were released by a cannon blast during a short near-massacre of Strayn's forces. Strayn himself was carted off to Bowling Green prison, but his dead me are resurrected and, zombified, start to march in search of blood and new recruits. I should mention here that Grey Knight's undead are a curious breed: Like vampires, they drink blood and increase their numbers by feeding on the blood of their victims. They're also unable to cross running water, vulnerable to silver, and only come out at night. However, they've got no fangs. They all wear white smears of what I suppose is meant to evoke the face paint of African tribal warriors. These undead are also vocal and intelligent, even emotional: They mourn when their own get killed.

After a few one-sided encounters, the remnants of the Union scout group end up teaming with the remains of a Confederate rear guard unit to fight the undead troops. There's a battle. Some people die. The end.

Questionable as the racial politics may be, far more crippling are the films visuals. Though Hickenlooper and Hellmann have a study and functional sense of narrative, the film has a dull, washed out feel to it. Whether this was the unfortunate result of an effort to give the film a faded, historical look or simply the result of a lousy color transfer, I couldn't say. The result is a milky, muted palate that drains life from the film far more effectively than the movies pseudo-vampires. Hickenlooper also fails to bring his combat scenes to life. Although early film effectively presented the madness of Civil War Era combat, filmmakers from the 1960s and on have too often relied heavily on the assistance of Civil War re-enactors. The result, aside from fielding armies of retired white collar workers, is that the combats have a sort of stagy calm. Hickenlooper's fight scenes feel leaden.

That said, there's something interesting in Hickenlooper's faint commitment to the story he's shooting. Despite setting up the clear premise that the undead troops are (literally) bloodthirsty monsters, Hickenlooper gives a handful of them some key speeches that, I believe, suggest the outline of the film he would have rather made. Strip away the monster movie trappings and, instead, imagine a band of Southern and Union soldiers who have gone rogue because they refuse to fight for either cause. The Southern boys don't want to die so rich folks can keep slaves. The Union boys don't want to die in a far off field for a cause they don't sincerely care about. Instead of putting down a semi-zombie outbreak, the scout unit is meant to find these dangerously freethinking individuals and crush their rebellion before it spreads to other troops. That story is, I think, what Hickenlooper wanted to do. His speeches about finding a third way out of the war, his attention to curious historical details, his refusal to embrace any of the larger moral issues of the conflict at the cost of an oddly myopic populism - it's when he's focusing on what he cares about, the flick gets a shot in the arm. Sadly, those bright moments aren't enough to carry the whole film.

Tuesday, December 29, 2009

Music: The preference of monsters.

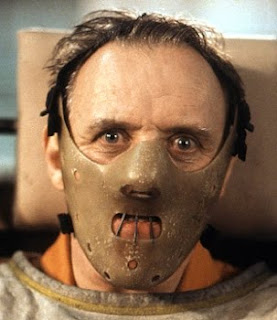

Classical pianist and blogger Jermey Denk ponders the role of classical music in horror flicks, with an emphasis on scenes from Twilight: New Moon and Silence of the Lambs.

As you can imagine, most of the music of Twilight is a spool of new age melancholy-lite with interchangeable aspartame chords and a spectacular disregard for monotony and cliché: the sort of thing you run across 12-year-old girls playing, to express themselves, on upright pianos in junior high chorus rooms after the last tater tots have been shoved down the last pimply gullet of the last smug bully before the last bus creaks out of the parking lot, sending wheezes of diesel sadness into the dusk as yet another chalky day of teaching scrawls to an end . . .

I was just settling in with my movie nachos, just getting used to this aural upholstery–anything that does not kill you, etc. etc.–when (suddenly!) a few notes reminded me that there might be a better world. Bella gets knocked against a wall, her arm’s bleeding and in a flash Dr. Cullen–a vampire who has virtuously pulled back his fake hair and steeled himself to resist his blood-urge–dismisses his weaker, ravenous vampire relatives, and prepares to stitch up her gaping wound. As he stitches, we hear [Schubert's setting of one of Goethe's poems, original post contains an audio file - CRwM].

This was no nacho hallucination! There really WAS a Schubert song lurking in this teen vampire romance … and not just Joe Schubert Song, but a setting of one of the greatest Goethe poems. But why this song? And why Schubert? My mind immediately and shamelessly ran after musicological ramifications: “Schubert is sucking at the neck of the subdominant, to demonstrate vis-a-vis the fangs of his modal mixture the inadequacy of conventional polarities of dominance” . . . Though I dismissed the notion of a hidden musicological agenda I suddenly wondered how many vampires take refuge in the musicology faculties of our nation’s universities.

This was one of these moments where Popular Culture decides for a capricious instant that Hundreds Of Years Of The Western Canon are temporarily useful for appropriation; it does classical music a huge favor by Noticing It. Lovers of classical music are supposed to beam and pant like a petted dog, grateful for any and all attention. Wag wag, woof woof, good boy, go play in your cute tuxedo now! Classical music often serves an iconic, representative, dubiously honorable purpose in popular film, and this instance of classical quotation–besides reminding me what a steaming load of crapola I had been listening to previously–reminded me very much of the famous scene in The Silence of the Lambs, where Hannibal Lecter brutally murders and partly eats his two guards to the strains of the Goldberg Variations.

In both these scenes, classical music becomes an emblem of distance and detachment. Cullen is looking directly upon blood without giving in to his hunger; he is practicing Zen-like separation from desire. Lecter has a very different detachment, the detachment required to kill perfectly, ruthlessly, without regret or remorse; his is the detachment, the disconnect, the absence of “normal” emotion which marks sociopathy.In both scenes, the music is ironic. It’s effective in a way that horrific or disturbing, i.e. “appropriate” music would not be. Its meaning lies in its otherness … While Lecter commits one of man’s darkest taboos (cannibalism), behind him rings the decorum and organization of Bach, with its peerless canons and schemes and rules; the Goldbergs whisper to our ears all the connotation and comfort of human Enlightenment, while the Dark Ages scream at our eyes from the screen. Cullen is stitching a raw wound; he fills a bowl full of blood … The camera lingers on both, in the way we imagine Cullen’s eyes unconsciously might; meanwhile the song proceeds in uncanny calm, a calm which feels strange against our sense of a repressed murderousness. The calm is a classical music calm, an alien calm, it evokes the price and pressure of Cullen’s self-repression. I have noticed often that the forces of Hollywood cannot use classical music to express “normal” emotions, but only extremes, only things that must be seen weirdly, in reverse.

In both scenes, blood. Both Lecter and Cullen traffic in blood, and their bloodiest scenes bleed classical music. Yes, we can say, the director is suggesting that classical music is “beauty” against which the horrors of bloodlust are seen more starkly. But if the music is supposed to be the opposite of the bloody scene, isn’t the implication somehow that the beauty of classical music is “bloodless”? Lecter is a soulless monster, and he loves Bach; Cullen is a soulless vampire, who uses Schubert to calm himself while he repairs a wound. Always soulless; always other; always anachronistic; classical music is the preference of monsters. I can see how the age of the music connects to the immortality of the vampire, I can see how the Bach connects to Lecter’s genius, but why must classical music be the language of monsters, of the fringe?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)