Have a little fun this weekend poking around Raymond Castile’s excellent Gallery of Monster Toys website.

Castile started the site in 1996 and, though the site doesn’t seem to have any place notifying visitors of the frequency of updates, the gallery has plenty to entertain the monster-minded. The site is organized into “wings,” each focused on a specific decade. Altogether, these wings offer the curious an idiosyncratic and delightful sampling of monster toys from the 1950s to the 1990s.

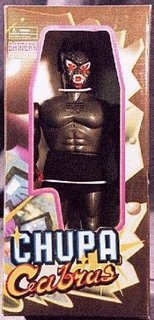

Personally, I think the best thing about the gallery is the seemingly random material that will pop up from time to time. Sure, fancy-targeted art dolls, such as the mini-statues cranked out by the likes of Todd McFarlane, appear on the site; but you’ll also find oddities like the freakin' kick-ass chupacabra doll shown below.

Saturday, November 25, 2006

Friday, November 24, 2006

Book: My money is on the giant, super-strong, un-killable guy.

I’ve praised the joys of mix-and-match style stories before. While I might be curious about a story containing Dracula, tell me that it features the Lord of Vampires going toe-to-toe with Al Capone and you’ve got my undivided attention. In The Shadow of Frankenstein, another in Dark Horse Press’s new line of Universal Monster tie-in novels, Stefan Petrucha offers readers just such a promising match-up: Jack the Ripper meets Frankenstein’s monster.

Unlike Di Filippo’s freewheeling and heavily revisionist take on the Creature from the Black Lagoon, Petrucha’s book is more overtly an extension of the Universal film franchise. It is meant to fall in between James Whale’s legendary The Bride of Frankenstein and Rowland V. Lee’s excellent 1939 follow-up, Son of Frankenstein. The novel begins with the Frankensteins, the mad doctor Henry and his long-suffering and increasingly unhinged Elizabeth, fleeing legal scrutiny and the hatred of the villagers in their native land. They are off to England with Minnie, trusty but annoying maid servant in toe. Unfortunately for them, the good doctor’s most famous bit of work tags along for the ride.

The Frankensteins and their eponymous monster get separated once they reach the shores of England. Henry, unable to let was he believes to be his dead monster rest, begins investigating the history of the brain he purchased to install within the creature. Meanwhile, the monster saves the life of a Whitechapel prostitute and is taken under her care. In one nice touch, the whores of Whitechapel, used to seeing the effects of urban squalor on their neighbors, find the monster’s horrific appearance somewhat unremarkable.

Into this mix comes Jack the Ripper. After years of retirement, the killer is once again stalking the streets of Whitechapel. Jack’s life, we discover, has been unnaturally prolonged through black magic. Sadly, for our active-senior/serial killer, the old spells just aren’t working like they used to. After encountering Frankenstein’s monster on one of his bloody patrols through the city, Jack comes to believe that, if installed in such a body, he could live forever. All Jack’s got to do is get the good doctor to see things his way. And, it turns out, Saucy Jack can be quite persuasive.

Petrucha’s novel is a fun, light romp through the universe created by the classic Frankenstein movies (and they are extremely movie-centric - if there was an allusion to the novel that started it all, I missed it). Petrucha sacrifices description and mood for a brisk and action-filled narrative that resembles less Whale’s surreal and atmospheric classics and more the crowd-pleasing, but less accomplished later entries in the series, such as 1944’s House of Frankenstein. His book is almost exclusively focused on getting his main characters into position and then letting all holy heck breaks loose. Along the way, he makes sure to hit all the archetypal scenes any self-respecting Frankenstein movie must have. You can almost imagine Petrucha with a check-list of required, archetypal scenes he needs to hit: “Body harvesting in the graveyard. Check. Frankenstein raging at God. Check. Kites training electrical wires. Check.” The presence of Jack the Ripper and the perceived needs of a presumably more bloodthirsty audience means we get considerably more gore out of Petrucha’s work than any classic Universal flick would give us, but all in all is stays true in spirit to the source material.

Not that Petrucha’s novel is without clever flourishes and nice touches. Lines from the classic films are recontextualized throughout the book to good effect. Nod and wink allusions are sprinkled about for the close reader – including my favorite, a short discussion on transferring the captured monster to Seward’s asylum. Petrucha also finds time, despite the pace of the book, to work in some excellent bits of characterization. Most notably, when we get an entire chapter’s worth of backstory on the man whose famously abnormal (“Abby someone”) brain was placed inside Frankenstein’s monster. That chapter is actually a stand out.

Overall, Shadow of Frankenstein is an entertaining tribute to classic horror icon. It is less innovative than Filippo’s entry to the series, though, if in a more narrow way, it is really no less enjoyable.

Labels:

books,

Frankenstein,

Petrucha,

Shadow of Frankenstein

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

Music: The Gruesomes for yousomes.

As regular readers already know, I’m a sucker for garage bands with any sort of gimmick. One of my favorites are the off-again, on-again Gruesomes, a garage revival outfit from Montreal. Taking the name of the Addam’s Family-like neighbors who appeared in The Flinstones, the band formed in 1985 and managed to build a fan base and crank out two EPs all in their first year. Their very first, titled Jack the Ripper, included an excellent cover Screaming Lord Sutch’s signature tune.

The Canadian music ‘zine What Wave interviewed the group in the pages of their eighth issue, scans of which are available online.

The band brought out three more LPs before packing it up in 1990. During their glory days, The Gruesomes only put out two videos: one for their wonderfully creepy “Way Down Below” and another for their more goofy Monkees-inspired “Hey!” I wanted to hit you with this Gruesomes twosome, but sadly I can only find footage of “Hey!” This means we're doing more silly than scary today, but lighten up Maurice, it's my blog and I'll roll like I feel.

If I ever find “Way Down Below,” I’ll post it.

The Gruesomes reunited in 2000, putting out a new album and touring in Canada. Garage archive label Sundazed Records has an amazing anthology of the Gruesomes that collects pretty much everything they did before the reunion. It is good stuff.

The Canadian music ‘zine What Wave interviewed the group in the pages of their eighth issue, scans of which are available online.

The band brought out three more LPs before packing it up in 1990. During their glory days, The Gruesomes only put out two videos: one for their wonderfully creepy “Way Down Below” and another for their more goofy Monkees-inspired “Hey!” I wanted to hit you with this Gruesomes twosome, but sadly I can only find footage of “Hey!” This means we're doing more silly than scary today, but lighten up Maurice, it's my blog and I'll roll like I feel.

If I ever find “Way Down Below,” I’ll post it.

The Gruesomes reunited in 2000, putting out a new album and touring in Canada. Garage archive label Sundazed Records has an amazing anthology of the Gruesomes that collects pretty much everything they did before the reunion. It is good stuff.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Movies: We prefer the term "metabolically challenged."

So, zombies. Maybe you’ve heard of them. The living dead. They’re kinda popular right now so like maybe you’ve seen them in a movie or read a comic book about them.

With the passage of the Zombie Mono-Culture Dominance Act of 2002, it has been a legal requirement that every third horror movie produced either in America or within the boarders of its NATO allies must be a zombie movie. The creators of the act would prefer it if the plot of the movie involved an unlikely group of survivors trapped and surrounded by the numberless legions of the dead. It is best if creative variation focuses on mobility issues (fast versus slow), the source of zombification (government screw-up versus ecological disaster), and the levels of gore reached. Otherwise, the more formulaic the better.

It is a sign, then, of how far US/French relations have disintegrated that France has produced one of the few truly original zombie movies to come out in the last four years. In fact, They Came Back (which, in France, goes by the considerably cooler name of Les Revenants) pushes the zombie-flick envelope ‘till it rips open.

The film, by writer/director Robin Campillo (who also co-wrote Time Out, a devastatingly eerie, but non-horror, psychological study of a laid-off white collar worker), starts right off with perhaps the most clichéd of zombie flick shots: a horde of the recently revived shuffling out of the local cemetery. Although, immediately, you notice a difference. These are not rotting ghouls. They are silent. Despite the fact that they number in the thousands, the only sound they make is the tread of their feet on the street leading into town. As the zombies reach the middle of town, the living gather to watch the strange sight. Some walk out to greet their loved ones, stunned to see them alive again. A voice over, which we later learn be the mayor’s voice, explains that somehow, all over the world, the dead came back. They are in perfect physical health. They seem to be mentally slower than their living counterparts, but for the most part they remember their lives. They want to go back to living with their families. They want their jobs back.

Throughout the rest of the film, we watch as the living, both on a personal and cultural scale, attempt to accommodate the dead. In the small town in which this film set, 130,000 recently dead people need reintegration. Worldwide, we’re told, the number is astronomical. On a personal level, what happens when your young child returns? Your lover of several years? Your wife?

To further complicate things, the dead come back physically well, but mentally there is something uncanny about them. Sometimes they seem pathetically retarded in their mental capacities. Other times, however, this quiet reserve seems sinister, as if they are patiently waiting for something.

They Came Back is not outright scary. There is no bloodshed. The “zombies” eat normal food and this they seem to do mainly to humor the living. Instead of a feeling of horror, Campillo builds a sustained paranoid and melancholic eeriness that is equal parts unsettling and heartbreaking. This he does through the slow accumulation of perfect little details. For example, when we are first introduced to the holding center that houses the dead while their loved ones come to get them, we get the striking and not immediately sensible image of uniformed soldiers painting blue lines on the floor of a gym. It takes a few moments to understand that they are setting up rows and rows of beds for what amounts to a flood of refugees. The images resonates with pictures from Katrina or the heat wave that struck Paris and this moment of recognition comes with a little extra punch because Campillo let the scene hang unresolved for a moment.

In a way, Campillo’s trust in the poetry of images over the power of narrative logic reminds me of his compatriot, Alexandre Aja. Both build emotionally valid impressions that, when they work, are strong enough to provide their own validation. Perhaps it is a French thing. Despite this similarity, it is impossible to imagine Aja creating a movie this subtle (or Campillo cranking out something as visceral as the circular saw/unlucky driver scene in High Tension). There’s another way in which this is a very French film. It seems to me that only France, with is secular semi-socialist ways would be more concerned about the effects of the returning dead on the pension system than they would be about whether or not returning from death yields any truths about life after death. Only one person, a nameless child character, asks one of the dead what it was like. Otherwise, everybody seems more concerned about how the return of dead relatives will effect their lifestyle. Seems to me that an American version of the movie would have talking heads arguing what this meant for religion, whether the dead would vote Republican or Democrat, and whether dead/living marriage is a sin. I’m not saying the latter would have been preferable. I’m just suggesting that it reflects a cultural difference.

Mermaid Heather, horror-blogger of note (see sidebar), has a policy of never giving out a perfect score for a movie unless it is actually scary. A movie might be technically flawless, contain great acting, and blah, blah – if it doesn’t bring the scares, then it doesn’t get the blue ribbon. This is a wise policy and, though I’ve broken this rule at least once already, I’m going to follow it here. As great a movie as They Came Back is, and as unnerving as it can be, it does not scare so much as unsettle. Therefore, using the Olympic Gold Performances of Amy Van Dyken handed down to me by my father and his father before him, I give They Came Back a 2000 Sydney 4 × 100 m freestyle relay. A winner of a film and certainly gold-worthy, but just short of a full 1996 Atlanta 100 m butterfly.

Labels:

Campillo,

Les Revenants,

movies,

They Came Back,

zombies

Sunday, November 19, 2006

Movies: People who need people (for foodstuffs) are the luckiest people in the world.

Cannibal Holocaust is something of jewel in the grindhouse crown. In a subgenre that takes pride in its ability to upset the cinematic sensibilities of the common Joe and Jane, Cannibal Holocaust holds a special place as one of those films that, in the words of the re-release trailer, "goes all the way."

After seeing it for the first time, I have to say that Cannibal Holocaust is one of those odd films that, at once, is both so much less than the rep that proceeds it and fully worthy of its reputation of as grade-A mind-fuck.

The plot (which is an acknowledged inspiration of the love/hate horror landmark The Blair Witch Project) features a professor from NYU who goes into the Amazon jungle in search of four American documentary makers who disappeared after they entered the jungle to film what they presume to be the last cannibal tribes in existence. He finds the footage of the first documentary crew and we learn that they pulled a Heart of Darkness trip, going insanely violent against the natives of the jungle before encountering, fighting, losing to, and feeding the cannibals they hoped to film.

The structure of the film is more complex than this plot summary suggests. Through a combination of flashbacks, faux documentary style footage, and standard narrative filmmaking, we jump back and forth between the various parts of the story. The film begins with a few minutes of the first expedition. Then we get the full story of the second expedition. Then, through a series of screenings of the first expedition's footage, we fill in the details of the first expedition. It is an effective narrative structure and works to build suspense even though the viewer knows before the end of first 30 minutes that first expedition didn't survive.

On many levels, Cannibal Holocaust is better than any movie with the title Cannibal Holocaust has the right to be. Filmed on location in New York and the Amazon, the sets are often breathtaking and, on multiple occasions, invest the exploitation proceedings with a strange and powerful beauty that exceeded what I'm certain were the filmmaker's intentions. Not that director Deodato can't set up a haunting shot. Even when he's not serving up gore by the truckload, Deodato wrings as much detail as possible out of his shots. One scene, for example, features two members of the first expedition engaging in some rough sex while the members of a native tribe they have previously attacked and terrorized watch silently in the distant background. The image is so stagey and its meaning so strange that tableaux of sex, domination, and sorrow sticks in the mind despite the lack of bloodshed. However, for the most part, Deodato's film sensibilities are overwhelmed by the power of his locations.

Deodato should also get some credit for the inclusion of some wonderful character moments. He captures excellent character moments: a wicked grin here, a worried look there. There's a surprising amount of subtle work in this film considering the number of times we're also treated to images of the characters vomiting.

For violence junkies and gorehounds, there's plenty to see. Characters are raped to death, torn apart, devoured, and otherwise discomforted. I didn't keep track of a body count, but those who enjoy having their senses assaulted are in for good time. This does, however, bring up the animal killings that the film is infamous for. In three scenes, Deodato filled the details of his actors killing animals. Deodato brought his same of love of detail to these scenes, so we're not talking about off-screen killings either. In the first incident, a small swamp rat of some sort is stabbed in the throat multiple times and then gutted. In the second, a large sea turtle is beheaded, dismembered and cracked open. Finally, a small monkey has its face chopped off and is bled (in the audio commentary, we're told by the director that the monkey's mate died shortly thereafter of what Deodato claims was a broken heart). These scenes, showing authentic death, ultimately undercut the special effects violence that appears throughout the movie. Ethical considerations aside for a moment, the rawness of these scenes emphasizes the falseness of the rest of the film. In the way the jungle trumped the filmmakers' skills, real violence trumped the filmmakers' moral imaginations. As a viewer, you'll care more about these three animals than you do about any of the human characters, and that, more than anything else, takes what might have been a film that transcended its grindhouse origins and reveals is tasteless, heartless, and exploitative core.

There's plenty more to discuss about the film: Vietnam conflict imagery, a sub-plot criticizing colonial exploitation, internal critiques of sensationalist media (believe it or not, the film actual includes a heavy handed critique of shock-for-shock's-sake entertainment), and more. The problem is that the levels of violence, the ruthlessness of the filmmakers' vision, and the raw nature of the real blood and guts spilled to make the viewer squirm all dwarf those considerations. Deodato has made a movie that is little more than a showcase for horrific violence and he did it so well that his attempts to stack ideological concerns on top – most often in the form of a sanctimonious speech by one of the leads – seems laughable. The violence mocks the philosophy.

Cannibal Holocaust is an exhausting, frustrating, and unsatisfying film. Its few grace notes hint at greatness, but are these moments ultimately drown in a sea of meaningless, exploitative, and genuinely brutal gore. Even its eagerness to shock works against it, as it often feels less like the work of a harsh but clear-eyed nihilist and more like the work of a hack who, when in doubt, simply pours fake blood everywhere. Though it must get some credit for representing something like the Platonic expression of the grindhouse aesthetic, its pleasures are narrow and, finally, shoddy. But that isn't the worst thing about the film. The most frustrating thing about the film is the teasing hints that it could have been better. Instead of being a monument to the gross-out MO of the exploitation crowd, it could have been the Apocalypse Now of horror cinema.

For fans of exploitation cinema, I recommend Cannibal Holocaust as the sort of logical conclusion of the genre's most common themes. For anybody else, the film is involving, but ultimately in a sort of disappointing and un-fun way. Using the famed Drums of Sri Lanka Movie Rating System, I give this flick a middling Hand Rabana, bumping it up to Bench Rabana to recognize its infamous and historic status.

Saturday, November 18, 2006

Book: "Even I, Lucas, have heard the legend of the Fish-Man. And I, Lucas, have read the book too."

Dark Horse, one of the longest running and most successful independent comic book publishers in the history of the medium, is no stranger to pulp tinged horror. For example, the Kirby-by-way-of-Lovecraft Hellboy comes out with Dark Horse's distinctive chess piece knight logo on the cover. The more frantic and over-the-top Goon is also a Dark Horse publication. Dark Horse also puts out a wide range of horror-related film adaptations. They've cranked out endless Aliens and Predator books. They even produced two issues of a Dr. Giggles book, believe it or not.

Dark Horse also does business in books of the non-comic variety, under the Dark Horse Press imprint. Here to, horror and licensed work is their bread and butter. Novels based on Aliens, for example, appear on the DHP backlist.

Recently, Universal Studios licensed their iconic stable of monsters to DHP. It is, in many ways a perfect fit. Novels based on the films Dracula, Wolf Man, Frankenstein (and his bride), and The Mummy are all in the works or already waiting for you on the bookshelves of you preferred vendor of fine readables.

The book that first caught my attention was DHP's Creature from the Black Lagoon tie-in: Paul Di Filippo's Time's Black Lagoon. Not being the biggest sci-fi fan, I don't recognize the names of many sci-fi authors, but Di Filippo's is one of the handful of guys whose work I'm familiar with. I read his Steampunk Trilogy with great pleasure, enjoy the reckless way Di Filippo blended high and low culture references, as well as the reckless, but ultimately respectful, way in which treated the various genres his works borrowed from. To me, his involvement in this venture was reason enough to take notice.

Time's Black Lagoon, like the Di Filippo's steampunk work, is a carefree mash-up of 50's horror, contemporary speculative fiction, and pulp action novel. Set mainly in the humid, post-climate change New England of 2015, the novel focuses on the adventures of Brice Chalefant, a marine biologist who, as the novel opens, has pretty much flushed his promising scholarly career down the toilet. At the end of a well-attended lecture on the impact of global warming on the environment, Brice went off on a tangent about how humans would be better equipped to handle the water-logged future if their genetics where altered to make them amphibious. This suggestion is soundly mocked and Brice goes from rising star to "the Merman Guy" overnight. However, not everybody at his university thinks he's nuts. The well-loved but eccentric Professor Hasselrude thinks Brice's fish-man idea is not only reasonable, he's seen it before. Turns out that Hasselrude was the nephew of the late Dr. Barton, the man who attempted to surgically alter the creature of permanent land-bound existence in the 1956 The Creature Walks Among Us. Hasselrude hips Brice to the history of the Gill-Man, suppressed and complete forgotten by 2015. The Gill-Man, they agree, would be the perfect template for Brice's theories. Unfortunately, the long-dead Gill-Man from the 1950s seems to have been the last member of Devonian species. It's another dead end for Brice until a friend of his, a DoD funded physicist working out of the University of Georgia, shows him what he's been working on: a time machine made out of an iPod. Suddenly, the Devonian is accessible and Brice and his significant bother, pro-outdoor guide Cody, mount an expedition to the Devonian. What they find completely rewrites the backstory of Creature of the Black Lagoon and opens up an entirely new mythology for the most neglected of Universal's famous monsters.

Like good pulp entertainment, Time's Black Lagoon aims to entertain. And on that level, it delivers. I suspect hardcore sci-fi fanboys will be disappointed in the lack of detail given such issues as time travel, but Di Filippo is less interested in science as he is in how science was presented in the wonderful sci-fi/horror flicks of the '50s. Despite the updated info about quantum physics and genetic manipulation and climate change, TBL is an intentional throwback to the '50s films that inspired it. Even the dialogue resembles that weird everything-is-a-speech dialogue that was a hallmark of classic sci-fi/horror. For example, on telling Cody he wants to study the Gill-Man, she tells Brice:

"Brice, I understand why you have to pursue this until you can't take it any further. It represents the possible culmination of everything you've been striving for. But all I ask is that you don't let it become an obsession, as it for Barton and the others. This creature and the knowledge it represents has ruined too many lives."

Of course it has sweetie; of course it has.

TBL never makes a bid to be anything other than a good time. It is unlikely that, even within Di Filippo's backlist, it will be considered a must read. But, for fans of pulpy fun and geeks of the Gill-Man franchise, it is well worth the admission price (about $7.00).

Friday, November 17, 2006

Comics: A cut above.

Previously in this humble little blog, I reviewed the first issue of DC/WildStorm's new Nightmare on Elm Street series and bemoaned the wussification of a title that, when it was home at the upstart indie press Avatar, was messy fun. To recap the situation for those who are just showing up: indie press Avatar had a deal with New Line Cinema that gave the comic publishers access to New Line's trio of slasher icons. Avatar produced several mini-series based on Friday the 13th, Nightmare on Elm Street, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. The Avatar books were clunky, but the covers were great, the action gory, and, all and all, the books were simple, gross fun. Earlier this year, somewhat unexpectedly and without much fanfare, New Line pulled their franchises away from Avatar and handed them to the much larger DC, home of Superman and Batman. DC's first New Line franchise series, Nightmare on Elm Street, hit the stands in October. The book was a big disappointment. The story was no better than anything Avatar produced and the art was worse than Avatar's. More significantly, the blood and violence had been tamed and toned down to the point where the book lacked any of the energy and force of the source material at its best. Given this lame first outing, I did not have high hopes for the other New Line series.

Previously in this humble little blog, I reviewed the first issue of DC/WildStorm's new Nightmare on Elm Street series and bemoaned the wussification of a title that, when it was home at the upstart indie press Avatar, was messy fun. To recap the situation for those who are just showing up: indie press Avatar had a deal with New Line Cinema that gave the comic publishers access to New Line's trio of slasher icons. Avatar produced several mini-series based on Friday the 13th, Nightmare on Elm Street, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. The Avatar books were clunky, but the covers were great, the action gory, and, all and all, the books were simple, gross fun. Earlier this year, somewhat unexpectedly and without much fanfare, New Line pulled their franchises away from Avatar and handed them to the much larger DC, home of Superman and Batman. DC's first New Line franchise series, Nightmare on Elm Street, hit the stands in October. The book was a big disappointment. The story was no better than anything Avatar produced and the art was worse than Avatar's. More significantly, the blood and violence had been tamed and toned down to the point where the book lacked any of the energy and force of the source material at its best. Given this lame first outing, I did not have high hopes for the other New Line series.The great thing about low expectations is that they are easily exceeded.

Shipping well ahead of schedule (the cover has a January '07 ship date on it) is the first issue of DC/WildStorm's new The Texas Chainsaw Massacre series and, unlike the lifeless Nightmare series, this one shows real promise.

The new series takes place one year after the events in the TCM remake of Hopper's classic. While I'm somewhat disappointed that the new series seems to have effectively become the new canonical ur-text for all future works, I'm not going a bitch and moan here 'cause New Line's got to promote their franchise and complaining that economics trumps taste (especially when were talking slasher-flick inspired comic books) is a waste of breath. After Leatherface chopped his way through a couple of cops in a supposedly secured crime scene and then vanished, the massacre at the Hewitt house became national news. For a year, local law enforcement gathered mountains of evidence, but was unable to find and apprehend the Hewitt family. Determined to give the outraged nation some sense of closure, a group of FBI cold case investigators shows up to take over the case. That's the plot so far. Simple, reasonable, and effective.

The art is suitably Rabelaisian. Along with the requisite blood and decay, we get vomit, trucks full of human remains, and generic sub-Deliverance levels of backwater squalor. The layouts can sometimes be inadequate to communicate the action and the line work is a bit sketchy (was there a rush to ship early?), but these flaws are relatively minor. The coloring has a drained look, which I feel is not a flaw as much as it is a nod to the sun-bleached colors of the original film.

The writing is crisp and efficient. Unlike the dialogue in the weirdly PG Freddy-themed series, these characters are allowed to swear, which is nice. Despite being set in the revised TCM universe, there is a nice nod to the original classic: the lead agent of the FBI team is named Hopper. All and all, a good little package that is a solidly pleasant read. Perhaps the best thing about the new series is the determination to expand the story with going into wild tangents. One of the major flaws of the Chainsaw franchise has been the relentless sameness of the plots. A group of kids, car trouble, saw, bad cop, dinner, escaped final girl, the end (or is it?). This basic plot showed up several times in the films and formed the basis of the Avatar series. By pitting the Hewitt family against armed and trained FBI agents who know what the Hewitts are and are gunning for them, at least we're promised a new sort of conflict. I understand the importance of fomula conventions in any genre, but the effort at variation is appreciated.

After the misstep that was the Nightmare series, this TCM adaptation is a massive improvement. On the strength of this debut, "Screaming" is officially going to upgrade the DC/New Line effort from "cause for regret" to "cautiously optimistic." Worth checking out, especially for fans of the franchise.

For the record, though, I still hope we get the Batman/Hewitt family cross-over.

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

Movies: "As a mass killer, I'm an amateur by comparison."

Chaplin's most enduring contribution to the collective imagination was the character of the Little Tramp. The bowler-wearing, cane-twirling persona that Chaplin wore through a considerable portion his career, not only survived the transition from silents to sound films, but managed to become shorthand for Chaplin's entire filmic output. In fact, the character is so essential to the legacy of Chaplin that the two are often conflated. As the film poster for the 1992 biopic attests, you want to evoke Chaplin, you just evoke the Little Tramp. It is something of a shock then to see Chaplin play Henri Verdoux, the title character of his 1947 film Monsieur Verdoux.

Herni, like the Tramp, is an awkwardly charming character. He also shares the Tramp's goofy fussiness. The Tramp, for example, can be fastidious about the flower on his lapel even when he is homeless and wearing trousers with holes in them. Similarly, Henri Verdoux stands on manners and an over-sensitive sense of social grace, especially in situations where they are comedically out of place.

However, there are crucial differences. The Tramp, while sometimes mischievous, exists in a world where human goodness is the ultimate end of all actions and the right can be expected to prevail. By contrast, Henri Verdoux is a nihilistic serial killer who, in his words, "liquidates members of the opposite sex."

That's right, in Monsieur Verdoux we get the odd spectacle the man responsible for creating the mostly cloying cutesy film character outside of a Disney flick eagerly playing the role of serial killer. Freaky, non?

The film, from an original idea of Orson Welles' and inspired by a true story, opens with a shot of Henri's gravestone and he explains, in posthumous voice over, that, for many years he was a bank clerk. However, he lost his job in the global Depression of the 1930s. Unable to find conventional employment, he explains in a matter of fact voice, he turned to killing women for their estates.

Cut to a thoroughly unpleasant family arguing about the fate of a relative. Seems she met a man in Paris, was caught up in a whirlwind romance, withdrew all her money from the bank, married the man, and then promptly disappeared. They debate calling the police, but decide to give it a few more days. They look at a photo of her husband, Chaplin with a humorously ugly little moustache, and one of the family members suggests the woman may have been murdered. This theory is promptly dismissed as alarmism.

Meanwhile, at a small country home in the south of France, Monsieur Verdoux is tending his garden. Behind him, ominously, a constant stream of thick black smoke pours from his backyard incinerator. We learn from the neighbors that he's been burning the incinerator for three days straight.

Viewers quickly get acquainted with Verdoux and his MO. Using several aliases, Verdoux criss-crosses France, seducing women and then dispatching them. Between these murders, Verdoux spends his days on a quiet country estate, enjoying the company of his wheelchair-bound wife and his young son.

It is the odd attractiveness of this charming monster, who takes the role of the film's hero without ever becoming anything but a villain, that is the chief pull of the film. Verdoux can be humorously meek. He's a vegetarian who carefully removes caterpillars from walkways, lest they get stomped, and chides his son for playing too rough with the pet cat. "You've got a vicious streak in you and I don't know where it came from," he tells his boy. But, on the job, which he refers to euphemistically as the "fight in the jungle," we see Verdoux sociopathically attempt to seduce a new victim while the body of the last is burned away in the incinerator out back. Verdoux is one of the founder fathers in that long line of smiling monsters that descends from this flick down through Tom Ripley on to Hannibal Lecter and Dexter Morgan.

The film itself is almost proto-Hitchcock, though you'll have to imagine a Hitchcock film in which the sympathies are almost entirely on the side of the killer. The murderous acts occur off-screen and the entire film is bloodless. Chaplin instead focuses on the manner in which Verdoux's plans are carried out or foiled. The comedy is dark and dry in tone. The plot, while adequate, is mainly a character study. The story contains several show piece scenes, including one in which Verdoux must confront a determined detective who is on to his game and another in which Verdoux meets a victim that causes him to question his own murderous ways. Ultimately, though, the suspense plays second fiddle to the pleasure of watching Charlie Chaplin relish the chance to play somebody evil. He had, in The Great Dictator (his film previous to this one), done a broad and devestating satire of Hitler, but that film was lightened by Chaplin's Tramp-like barber, the safe and familiar character serving as the film's comforting moral core. In Verdoux, Chaplin does away with the counterpoint, letting Verdoux's greedy brand of malignancy take center stage.

Though this lacks the violent kicks that attract folks to modern serial killer flicks, I dug this flick and cannot recommend it highly enough. Using the celebrated Five General Classifications of Bones Movie Rating System, this flick gets a full and unqualified Sesamoid rating. You read that right: Sesamoid!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)